Intricacies of inquiry

Public inquiries are a core component of modern democracies. agendaNi explores the intricacies of what is often an oversimplified and misread process of investigation.

Often in the immediate aftermath of a controversial event, one predictable reaction is the demand for a full and public inquiry or a judicial inquiry (one that is chaired by a leading member of the judiciary).

The concept of an independent public inquiry is an ambiguous one. British Cabinet Office advice states that an inquiry can be undertaking for several reasons. These include: establishing the cause of a major disaster, accident or event leading to a significant loss of life and or damage; making recommendations in order to learn lessons from such an incident; and investigating serious allegations relating to public concern which require impartial investigation beyond normal criminal processes.

Judges or retired judges are often, though not always, appointed to chair both statutory and non-statutory inquiries due to their neutral standing (independent of any political allegiance) and experience of handling witnesses and procedural minutiae. Nonetheless, there is a potential for judicial independence to be dented through such an embroilment in political controversy.

William Laming, who chaired the Victoria Climbié Inquiry in 2001 noted: “[Inquiries] should improve our understanding of complex issues. At best they change attitudes, policies and practice. That being so, they occupy an important place in our society.”

However, an alternative and cynical view argues that the establishment of an inquiry can facilitate more deviant rationale. For example, kicking an issue down the road, blaming preceding government ministers, an overarching engagement in gesture politics or simply a mere buckling under public pressure. Michael Heseltine once stated: “No government wants inquiries; they are usually in circumstances where the Government is in trouble… They are not popular things for governments.”

As far back as the late 17th century inquiries have been conducted into British Government failures. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, inquiries were conducted by select committees into the actions of individuals, organisations, the Government and its officials. In the 20th century this had evolved into a process of appointing judges to chair public inquiries into issues of public concern.

Most commonly a public inquiry refers to those inquiries which are established by Government ministers. Appearing before the House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee concerning Government by Inquiry in 2004, Geoffrey Howe identified six functions of public inquiries:

- establishment the facts – providing a full and fair account of events, especially in disputed circumstances;

- learning from events – attempting to avert a recurrence through the distillation of changed practice;

- catharsis – creating an opportunity for resolution and reconciliation;

- reassurance – rebuilding public confidence;

- accountability – holding individuals and organisations to account; and

- political consideration – serving a wider political agenda for government either to effect change or to present proactive face.

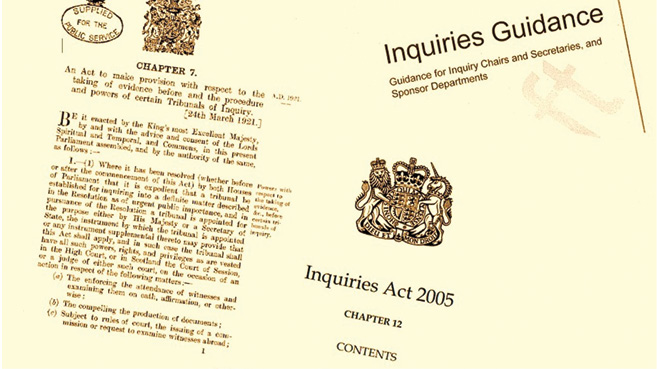

Public inquiries can be broadly separated into two main categories: statutory and non-statutory. The majority of statutory inquiries are held under the Inquiries Act 2005. Often the lines between the two categories can be blurred with each acting quite similarly. However, there are three crucial differences between a statutory and a non-statutory inquiry:

1 non-statutory inquiries rely on the voluntary compliance of a witness;

2 a non-statutory inquiry cannot receive evidence on oath; and

3 statutory inquiries always occur under the presumption that hearings will take place in public.

Statutory

Up until the implementation of the 2005 legislation, the statutory framework of independent public inquiries was outlined by the Tribunal of Inquiry (Evidence) Act 1921.

A public inquiry as defined by the Inquiries Act 2005 receives evidence and conducts hearings in a sphere accessible to the public. Under legislation a public inquiry can both compel the release of documents and the appearance of witnesses to provide evidence.

The decision to initiate a public inquiry is a political one and as such is subject to a number of factors including media coverage. Due to the requirement to meet statutory conditions, public inquiries can be an arduous process requiring a significant period of time in which to compile a report and, subsequently, can prove to be costly.

Non-statutory

Non-statutory inquiries can adopt three main formats: ad hoc inquiries, inquiries by the Committee of the Privy Council or Royal Commissions. They do not have the legal basis to compel the appearance of witnesses or the disclosure of documentation. Nor are they bound by procedural rules or required to conduct proceedings in a public arena. As such, terms of reference must be agreed upon among the involved parties.

However, this ensures enhanced flexibility for those involved in determining an inquiry’s procedures. They can facilitate a more investigative and less confrontational style of inquiry, while they can also be deployed to ensure that evidence concerning sensitive issues, such as security, can be heard in private.

This non-statutory style of inquiry was used extensively in Britain during the 20th century in order to investigate specific and controversial events of national concern. One such instance which relates to Northern Ireland was the Maze Prison Escape Inquiry (1983-84).

From the 1970s onwards, non-statutory ad hoc inquiries became increasingly common. Before 2004, a mounting perception of statutory inquiries under the 1921 legislation indicated that these were excessive and unwieldly. As such, non-statutory inquiries became the method of choice for investigation of the Government or public bodies. Indeed, even following the ratification of the 2005 Act, non-statutory inquiries continue to be utilised.

The Inquiries Guidance issued by the Cabinet Office emphasises that there is no assumed predominance between statutory and non-statutory ad hoc inquiries. Instead, the guidance recommends that advice be sought from the Cabinet Office Propriety and Ethics Team on the merits of each option.