Skills and regional balance

A “missing middle” of those possessing medium level qualifications appears to be one of the most pressing challenges facing each of Northern Ireland’s regions as the economy looks to rebuild at the beginning of a decade rocked by Brexit and Covid-19.

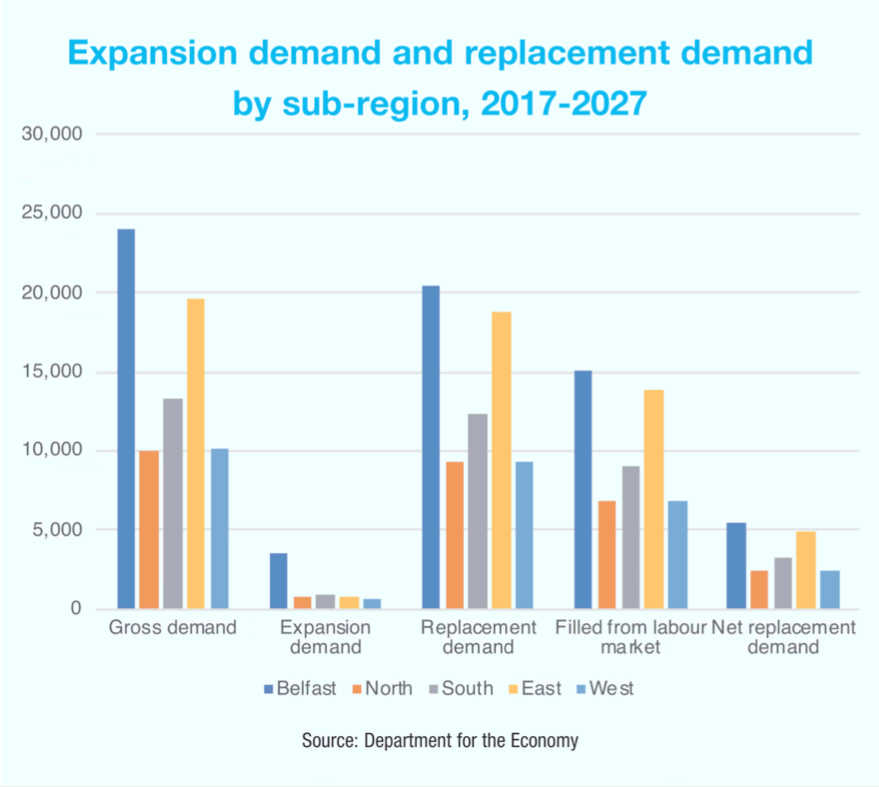

In a 2019 series of sub-regional skills barometers compiled by Ulster University and the Department for the Economy, each of the five sub-regions were found to have a “missing middle”, a lack of those with qualifications between National Qualification Framework (NQF) levels 3-5 forecast to enter the labour market in the decade 2017-2027. In the Belfast area, it said that “most” people in possession of these qualifications proceed onto further study, in the North sub-region (a combination of Derry City and Strabane and Causeway Coast and Glens council areas), 43 per cent of those possessing the qualifications were projected to do the same.

In the South sub-region (Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon and Newry, Mourne and Down), only 26 per cent of those so qualified are forecast to enter the labour market, while demand is forecast at 39 per cent. In East (Mid and East Antrim, Antrim and Newtownabbey, Lisburn and Castlereagh and Ards and North Down), demand for NQF levels 3-5 qualified employees is predicted to be 38 per cent, but the rate of those entering the labour market is forecast to be 27 per cent.

Similar to Belfast, the West sub-region (Fermanagh and Omagh and Mid Ulster) is predicted to also have a shortage of mid-level qualifications due to those possessing the qualifications progression onto further study.

Compounding this missing middle is an apparent unwillingness within adults in Northern Ireland to participate in lifelong learning. The OECD report found that only 18 per cent of adults here indicated a willingness to do so, compared to the OECD average of 24 per cent and England’s rate of 25 per cent. Commitment to upskilling and retraining will be necessary in the decade to come as an OECD report predicts that the main challenges for Northern Ireland will be digitalisation, demographic change, globalisation, and Brexit.

The OECD skills strategy for Northern Ireland has found that the region “has made significant progress in strengthening its skills and economic performance” in recent years but warns that “the Covid-19 pandemic will likely reverse much of this performance”. The report states that skills policies will be an “essential component” of any exit strategy from the damage wrought by the pandemic. Skills development, it states, “can have a positive impact on the economic recovery, and a resilient and adaptable skills system can help to mitigate economic and social shocks in the future and could help to prepare for challenges posed by megatrends”.

In terms of challenges, the OECD found that Northern Ireland “continues to experience high rates of economic inactivity”, with a labour productivity rate that is 17 per cent lower than the UK average, and an economy characterised by large, low value-added sectors and current and projected skills imbalances.

“In terms of challenges, the OECD found that Northern Ireland ‘continues to experience high rates of economic inactivity’, with a labour productivity rate that is 17 per cent lower than the UK average, and an economy characterised by large, low value-added sectors and current and projected skills imbalances.”

There is hope that the city deals of Belfast (which covers six council areas) and Derry City and Strabane (covering a seventh area) will deliver the type of investment needed to address these imbalances. The Belfast Region City Deal features the City Deal Apprenticeship Programme, a framework to pilot new approaches in priority areas such as digital, manufacturing, health, construction, and tourism sectors. The City Deal also features the Digital Skills Programme, aimed at creating a “pipeline of talent” to address the digital skills shortage in the region.

Similarly, the Derry City and Strabane City Deal features investment in programmes such as the Apprenticeship and Skills Hub, the Skills Growth Fund, the Youth Investment Programme, the Intermediate Labour Market Programme and the Integrated Work and Health Programme. These investments are aimed at increasing the skills capacity and addressing the economic inactivity within the region, with the Apprenticeship and Skills Hub planned as a “one stop shop for targeted investment in apprenticeships and skills focused on key sectors such as digital/IT and advanced manufacturing”.

OECD research has previously found Northern Ireland to be the region of the UK most at-risk in terms of job losses through automation. Manufacturing and agriculture jobs are known to be under an especially grave threat, which does not bode well given that Belfast is the only one of the five sub-regions where the manufacturing sector is not a top five sector for employment. The West sub-region could be hit hardest, with the manufacturing sector the largest employer in the area and agriculture the fifth biggest.

A large increase in pensioners looks to be a key challenge for the economy to meet, with the share of people aged 65 and over expected to rise from 17 per cent in 2020 to 21 per cent by 2030. Of the local government areas, Causeway Coast and Glens (29 per cent), Ards and North Down (30 per cent) and Fermanagh and Omagh (28 per cent) had rates of workers aged 50 and over higher than the average (26 per cent) in the 2011 Census, meaning they are the areas most under threat in this regard.

In terms of Brexit, as NISRA reported in 2019, 57 per cent of Northern Ireland’s exports go to the EU, 38 per cent to the Republic of Ireland, and this threatens almost all sectors. The OECD writes that the subsequent “economic disruption may be deeply felt” but also that Brexit may “open a number of new positive scenarios” and that “where tighter rules over immigration may create skills pressures for employers, they may also generate better job prospects for adults who are able to develop the skills in demand”.

The OECD’s Skills Strategy contains within it four key recommendations to strengthen the Northern Ireland skills capacity in the wake of these challenges: reduce the skills imbalance through funding model reforms and a regional approach to attracting skilled migrants; create a culture of lifelong learning by publishing a single strategy for adult learners, establishing a ring-fenced skills fund and extending the offering of blended education; transform workplaces to make better use of skills by developing a new strategy for management and leadership capabilities, ensuring sufficient provision of management and leadership programmes within micro and small business and improving information on business support programmes; and strengthening the governance of skills policies by committing minister and decision makers to sustainable funding for skills, increasing co-ordination in skills policy by introducing a capital oversight body and implementing a central skills needs advisory body.