Recession and recovery

Predicted economic recession is beginning to formulate in official data, however, the extent and lasting impacts of the recession are still not clear.

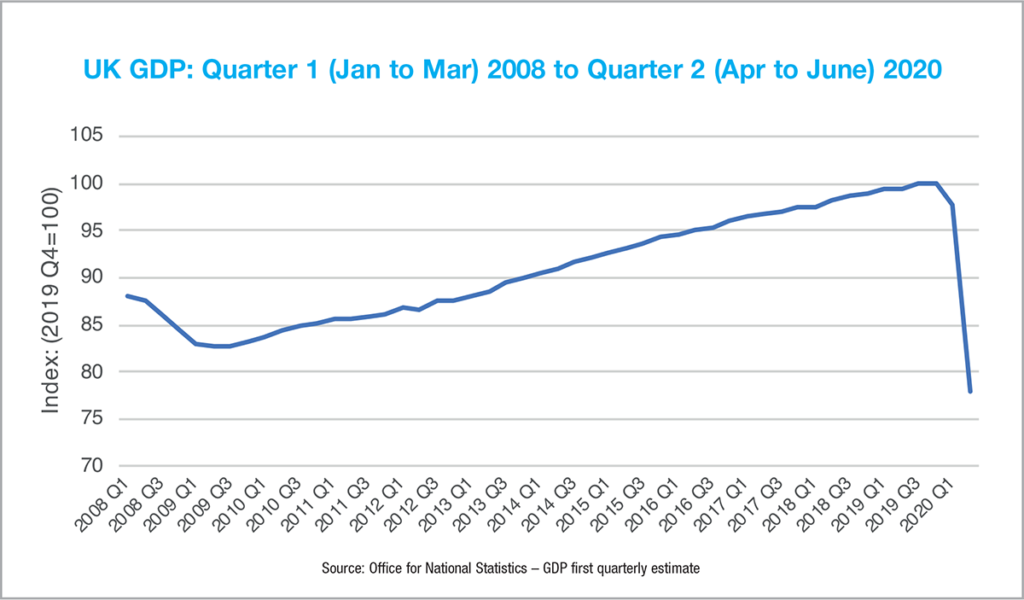

In August, the UK officially entered recession for the first time in 11 years and recognised its biggest slump on record between April and June.

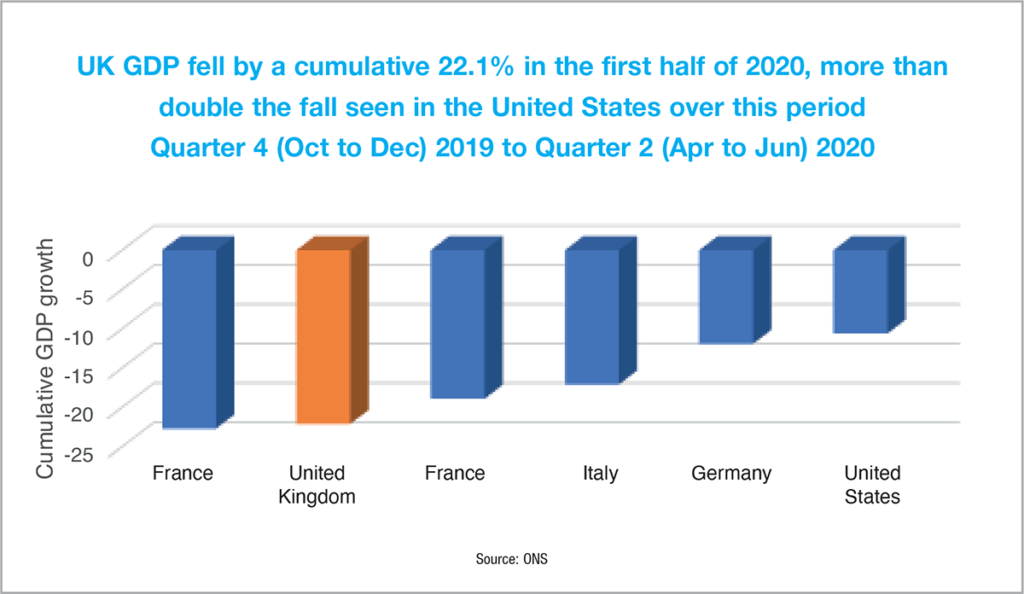

A 20.4 per cent shrinking of the economy compared to the first three months of the year contained the first two consecutive quarters of economic decline since 2009 and saw the UK recognised as suffering one of the deepest recessions across Europe.

Monthly GDP rose by 8.7 per cent during June 2020 but the profoundness of the recession was recognised in that even after this growth, levels were still 17.2 per cent below February 2020 levels.

The far-reaching extent of the pandemic’s impact on global economies was emphasised in early September when Australia, the only major economy to avoid a recession during the 2008 financial crisis, recognised a 7 per cent shrinkage of GDP between April to June, its first economic recession in almost 30 years.

Economists, having learnt lessons from 2008, recognise that the backward looking data collected on GDP often masks the current economic climate, meaning that economic recession is often well underway by the time two consecutive quarters of decline are recorded.

A forecast by the City of London economists predicts a 14.3 per cent increase in the third quarter of 2020, reversing over half of the drop in output in the three months to June.

However, unlike the financial crisis, economic recession has been far more widely predicted given the extent of the lockdown restrictions imposed across most sectors. Many had hoped that the forced nature of economic freeze would make for a greater level of rebound once restrictions were lifted.

While it has been the case that the UK’s economic activity has improved over the summer months, narrowing the gap between the UK and of its neighbouring European countries, Prime Minister Boris Johnson warned in early September that the UK’s economic outlook was “about to get tougher”, with Chancellor Rishi Sunak admitting tax rises would be required to pay for the economic chaos wrought by coronavirus.

Hopes for a quick rebound, although highly unlikely to meet pre-pandemic levels for many years, were bolstered in August by a stark rise in consumer spending across the UK, while still remaining down across the year. A forecast by the City of London economists predicts a 14.3 per cent increase in the third quarter of 2020, reversing over half of the drop in output in the three months to June.

Retail sales were up 3.6 per cent in July from June, higher than the same month the previous year and for the first two weeks of August consumer spending was around 7 per cent higher than during the same period in 2019. However, also recognisable is that there are question marks over the sustainability of this spending given that the UK imposed restrictions longer than many other economies. Also to be factored in is the level of government supports which are set to come to an end. The ending of the furlough scheme is a prime example, when a spike in the unemployment rate is unquestionable once employers no longer have government backing. Additionally, the Government’s eat out to help out scheme, recognised as a success, will have bolstered economic recovery figures but spending patterns are unlikely to remain the same now that the scheme has ended.

The return of schools however, a significant contributor to economic output, may provide an economic boost in future data. Even a record-breaking third quarter will not be enough to bridge the deficit driven by the pandemic. Pent up demand in some growth sectors is expected to subside. At the same time, uneven growth, underpinned by the failure of a large percentage of office workers to return to their offices, is expected to continue for the foreseeable future and existing weaknesses, such as business investment uncertainty caused by Brexit are set to be exacerbated, coupled with the large rise in unemployment.

Northern Ireland

Historically speaking, contraction of the Northern Ireland economy tends to be greater than that of the UK average. Also evidenced by the last recession, is Northern Ireland’s slowness in recovery when compared to Great Britain or Ireland.

Danske Bank recently predicted an 11 per cent shrinkage of Northern Ireland’s economy due to the impact of Covid and coupled with estimates that Northern Ireland took seven years to recover lost GVA from the last recession, it’s unlikely that Northern Ireland can expect the same level of economic bounce back being hoped for in the rest of the UK.

The challenges facing Northern Ireland’s economy are numerous but not least is a recognised productivity gap compared to other regions. As a low productivity economy, Northern Ireland relies heavily on the likes of retail and hospitality as large employment sectors, many of which have been hit hardest by the pandemic.

Again, the backward looking nature of economic analysis means that the full extent of the economic decline being experienced in Northern Ireland will not be fully realised until later in the year. However, a measure of how extreme the decline will be can be partially viewed through the lens of trends in the labour market, including the levels of those economically active and rising levels of unemployment.

The most recent statistics by the Northern Ireland Employment and Research Agency (NISRA), released in July, only cover the first quarter of 2020 to March, meaning the figures only reflect a few weeks of economic restrictions imposed as a means to tackle the virus.

The figures show that economic output decreased by almost 3 per cent from the last three months of 2019 and this represented a 3.2 per cent decrease in real terms over the year from the same period in 2019. The decrease was driven by drastic slowdowns in the services, productions and constructions sectors. The decreases in Northern Ireland were larger than the UK averages both over the quarter (2.8 per cent in Northern Ireland compared to 2.2 per cent UK average) and over the year (3.2 per cent in Northern Ireland compared to a 1.7 per cent UK average).

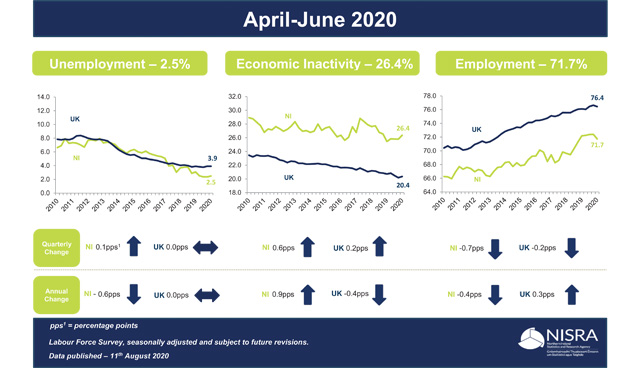

Probably more telling but still limited in its data range to assess the full impact of the economic impact of the pandemic is the doubling of Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate from March to July.

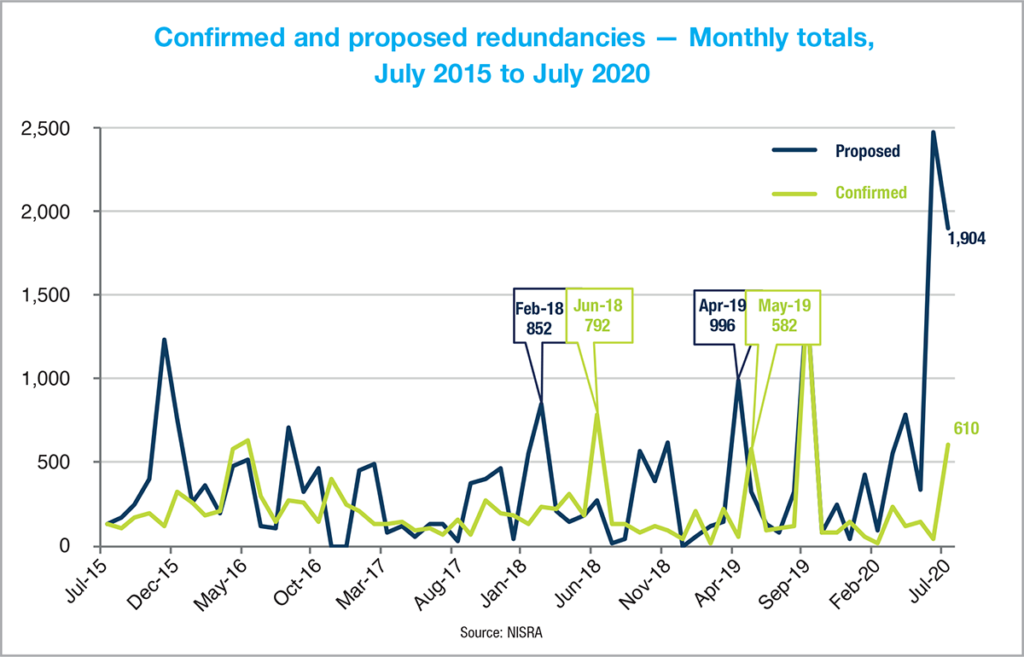

Statistics show that the claimant count rose from 29,000 to 62,800. Over 2,000 redundancies were proposed in July and the first two weeks of August, meaning that the 8,755 redundancies proposed over the year from August 2019 to 31 July 2020 was the highest on record. That figure has already increased, although this has not yet shown on official figures. From August, employers have had to make financial contributions to the Government’s furlough scheme and this has resulted in a high proportion of jobs, and businesses, being declared as unsustainable. It’s estimated that at the end of August, 330,000 were receiving some sort of income support from London.

The decreases in Northern Ireland were larger than the UK averages both over the quarter (2.8 per cent in Northern Ireland compared to 2.2 per cent UK average) and over the year (3.2 per cent in Northern Ireland compared to a 1.7 per cent UK average).

The redundancy figure is set to spike again when the furlough scheme and self-employment support scheme come to an end. The largest challenge facing Northern Ireland’s economic growth ambitions is that a rise in redundancies is set to be coupled with a less than buoyant job market. This was partially indicated by a 52 per cent decrease in the number of job vacancies notified between April and June 2020 compared to January and March.

There were 7,911 vacancies notified during April-June 2020, a decrease of 8,494 (52 per cent) from January-March. This includes full-time, part-time and casual vacancies. Three quarters of vacancies were full-time.

Worryingly, Northern Ireland’s higher than average economic inactivity rate (the proportion of people aged from 16 to 64 who were not working and not seeking or available to work) increased over the year to 26.4 per cent, compared to a UK rate of 20.4 per cent.

The trend of rising unemployment and job losses is expected to continue until 2022, at the earliest. In late August the Department for the Economy said that a “conservative estimate” was for more than 100,000 unemployment claimants by the end of 2020.