Rape and consent: ongoing challenges

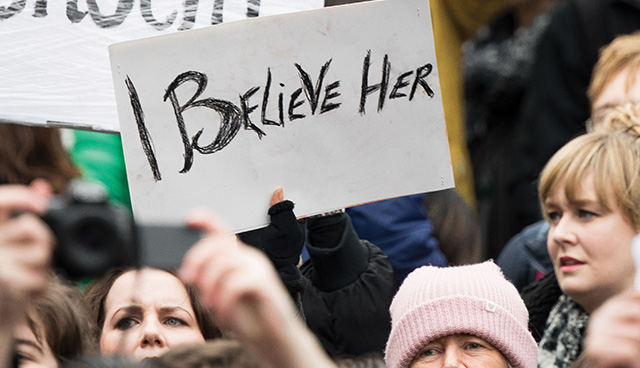

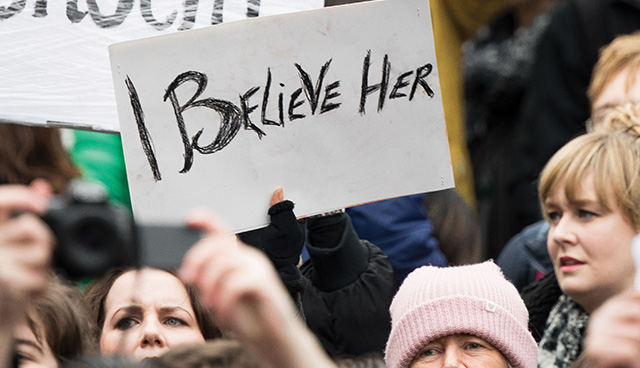

In the context of the recent high-profile rape case involving two former Ireland rugby internationals, among others, Eithne Dowds, a lecturer in the School of Law at Queen’s University Belfast, writes on the topic of sexual consent and rape.

Historically, proving the crime of rape was dependent upon evidence of the use of physical force by the perpetrator, as well as clear signs of resistance on the part of the victim. In contemporary rape law, many jurisdictions now consider consent as the essential consideration in establishing the offence (MC v Bulgaria 2003 Application no. 39272/98).

Historically, proving the crime of rape was dependent upon evidence of the use of physical force by the perpetrator, as well as clear signs of resistance on the part of the victim. In contemporary rape law, many jurisdictions now consider consent as the essential consideration in establishing the offence (MC v Bulgaria 2003 Application no. 39272/98).

Questions surrounding how the concept of consent ought to be interpreted and applied, however, remain contested: what precisely does consent mean and how can consent or lack thereof be proven?

In Northern Ireland, the law on rape and consent is governed by the Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008 which mirrors the Sexual Offences Act 2003 for England and Wales.

According to Article 5 of the 2008 Order, to establish the crime of rape the prosecution must prove that the sexual activity took place without the complainant’s consent and that the defendant did not reasonably believe that that person consented. It also provides that reasonableness will be determined with reference to the surrounding circumstances, including any steps taken by the accused to ascertain consent. The introduction of the reasonableness standard is a welcome development, as, prior to the Order, a defendant could escape liability if he honestly believed the complainant was consenting, even if that belief was unreasonable (DPP v Morgan [1976] AC 182).

Article 3 of the Order also moves the law forward by providing a statutory definition of consent requiring that the person agrees by choice and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice, as opposed to relying on its ‘ordinary’ meaning, as was the position under common law (R v Olugboja [1982] QB 320).

The meaning of consent, or absence thereof, is further illuminated by the inclusion of a number of circumstances where it is presumed that the victim did not consent to sexual activity and the defendant did not reasonably believe that the victim consented. Article 9 provides that there will be an evidential presumption against consent where the victim has, for example, been subject to violence (may be rebutted by the defence). Article 10 provides for a conclusive presumption (cannot be rebutted) where, for example, it is established that the defendant intentionally deceived the complainant as to the nature or purpose of the relevant act.

Myths and stereotypes

While these developments are encouraging, their progressive application is dependent upon broader social attitudes around what amounts to acceptable socio-sexual behaviour.

Complicating matters is the existence of various problematic rape myths. For instance, a 2008 report by Amnesty International found that 44 per cent of Northern Ireland university students believed a woman is responsible (partially or totally) for being raped if she was drunk; 46 per cent of respondents believed that a woman is totally responsible or partially responsible for being raped or sexually assaulted if she has acted in a flirtatious manner; and that 48 per cent of students believe that a woman is partially or totally responsible for being raped if she failed to clearly say no.

These statistics point to a culture of victim blaming, directing attention to the actions of the complainant and whether there is anything about those actions that could have induced a reasonable belief in consent. In this regard, individuals who do not conform to idealised notions of victimhood or the ‘real rape stereotype’ i.e. the young virginal victim violently overpowered and attacked at night by a stranger, are disbelieved or deemed less worthy of legal protection (Estrich 1987).

Such myths and stereotypes are however manifestly unfounded and, indeed, legally inaccurate. For instance, many survivors of rape have reported feeling unable to move and freezing during the attack (Lodrick 2007) and the law does not require victims of rape to positively dissent, protest or resist to prove the absence of consent (R v Malone [1998] 2 CAR 447; MC v Bulgaria 2003 Application no. 39272/98). The UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women has also openly rejected the application of such misconceptions (Vertido v The Philippines (Communication No. 18/2008)).

As such, there is a divide between the law as it appears in statute or case-law and how it is perceived in popular opinion. This divide can then be exploited by defence lawyers who often perpetuate rape myths in an attempt to undermine the credibility of the victim and attach ‘reasonableness’ to the actions of the defendant: Why did they not fight back? What prevented them from shouting out to attract help? (Rt Hon Dame Elish Angiolini 2015).

Such defence strategies lead to secondary victimisation, reinforce problematic attitudes and do little to enhance broader understandings of consent and rape. This is particularly worrying in light of research carried out by the Student Consent Research (SCORE) Collaboration – a student-led organisation at Queen’s University Belfast. In 2016, SCORE found that 177 out of the 3,097 (5.7 per cent) students were unsure if their experience amounted to sexual assault.

Moving forward

To overcome these challenges, Northern Ireland should draw lessons from international and comparative law.

Reforming the legal definition of consent to reflect the ‘equality approach’ that has been advocated in international human rights law, for example, might help to counter these stereotypes and problematic defence strategies.

The equality approach starts by examining not whether the woman said ‘no’, but whether she said ‘yes’. Women do not walk around in a state of constant consent to sexual activity unless and until they say ‘no’, or offer resistance to anyone who targets them for sexual activity. The right to physical and sexual autonomy means that they have to affirmatively consent to sexual activity (Submission of Interights to the European Court of Human Rights in the case of M.C v Bulgaria, para 12).

This approach requires the perpetrator to actively seek and positively obtain consent, representing a more respective and communicative model of consent.

A new law passed in Iceland takes a similar approach making sexual relations with a person illegal unless they have given their explicit consent, and variations of this model are evident in the case law of the Supreme Courts of Ireland (Director of Public Prosecutions -v- O’R [2016] IESC 64) and Canada (R v Park (1995) 2 S.C.R. 836), as well as legislation in the US State of Wisconsin and proposed reforms to the law in Sweden.

In general, however, reform to the law will be of limited value unless there is investment in training and education for criminal justice actors, as well as the wider public, on rape, consent and the associated misconceptions. It is imperative that positive understandings of consent do not remain hidden in legislation but are brought into everyday conversations on what does and does not amount to appropriate socio-sexual behaviour.

References

Amnesty International, Violence against women: the perspective of students in Northern Ireland, September 2008.

Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland, Policy for Prosecuting Rape, December 2010.

Rt Hon Dame Elish Angiolini DBE QC, Report of the Independent Review into The Investigation and Prosecution of Rape in London, 30 April 2015.

S. Estrich, Real Rape: How The Legal System Victimizes Women Who Say No (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987).