Better than expected but less than needed

Ulster University Economic Policy Centre’s Gareth Hetherington analyses the economic outlook as we enter the critical Article 50 negotiation period.

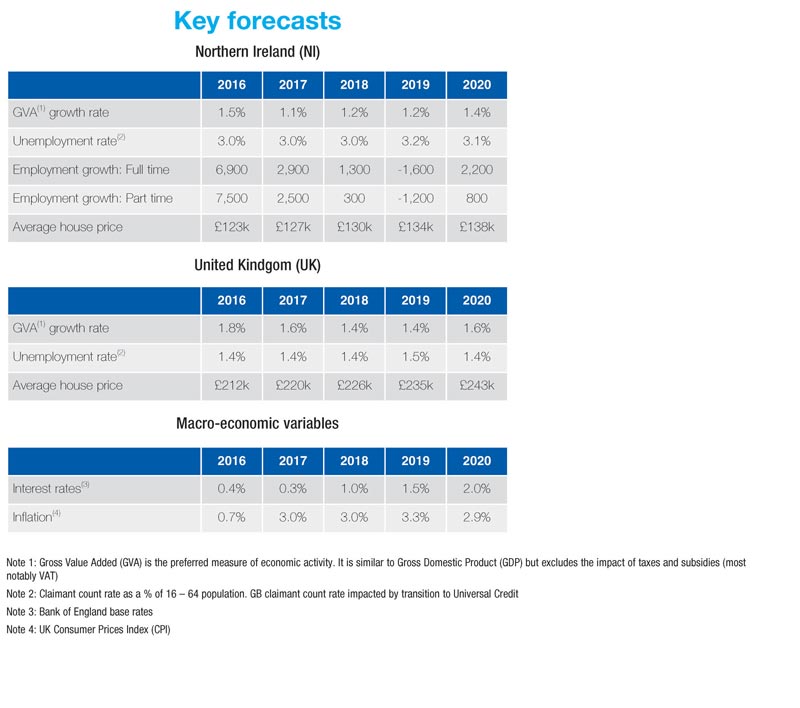

The economic performance both locally and nationally in the wake of the referendum result last June has been stronger than many had anticipated. However, more recent economic indicators are suggesting a cooling in growth and given the ongoing uncertainties following the General Election, there is no room for complacency regarding the economic outlook.

The primary risk to economic growth in the short-term remains a squeeze on incomes and the subsequent impact on consumer spending. The longer-term impact will be entirely dependent on the final Brexit deal negotiated and subsequently with other international trading partners. It is around these trading relationships that the greatest level of uncertainty exists.

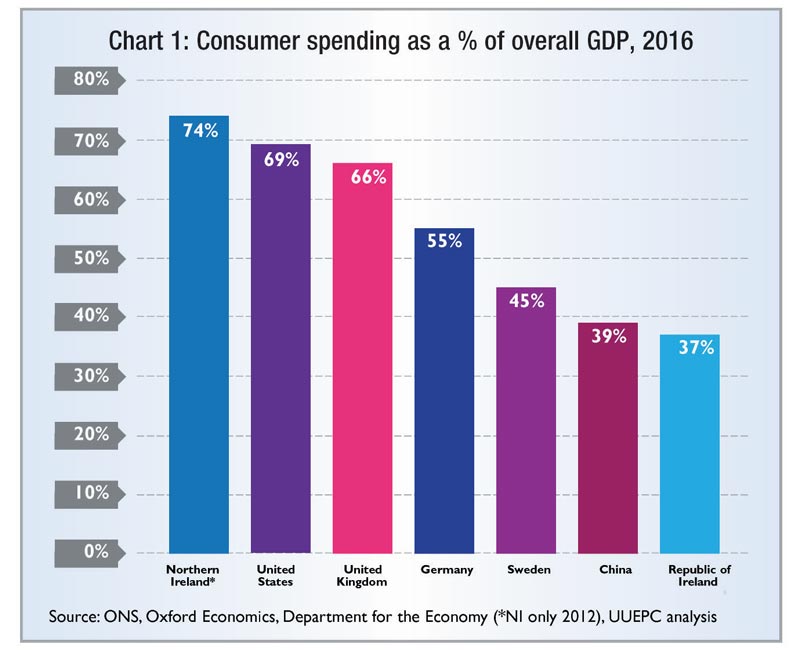

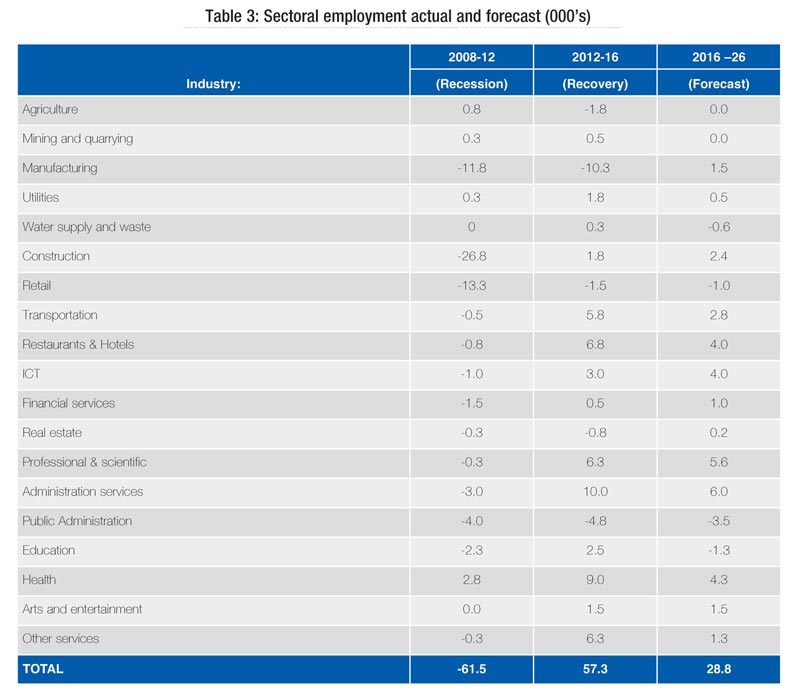

Forecasting is a challenge at any time, but in the current environment a much wider range of outcomes is possible. Whilst, the most likely outcome is for the creation of approximately 29,000 jobs over the next 10 years, a damaging and poorly coordinated Brexit combined with a squeeze in real incomes could see employment levels fall by 8,200 in the same time period. In contrast, a trade-friendly smooth transition Brexit combined with convergence with UK average economic performance could see employment levels increase by 87,500 by 2026.

Critical role of the consumer

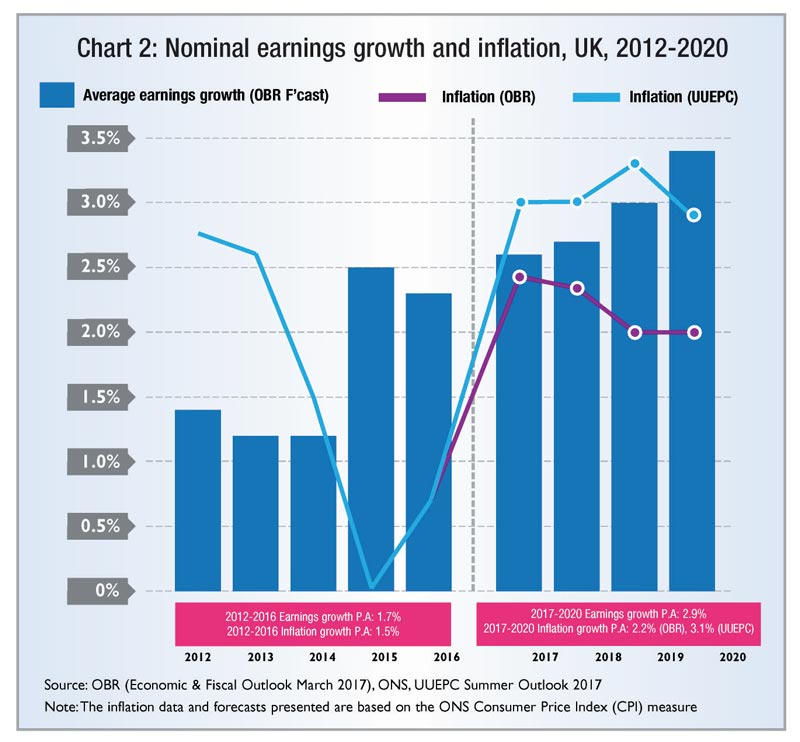

Returning to the short term issue of consumer spending, the UK and Northern Ireland economies are more reliant on consumption as a driver for economic growth than many other advanced nations (see Chart 1). By way of example, trade is a more significant component of growth in the Republic of Ireland and Germany, given their strong export focus. Therefore, from a UK perspective, continued economic growth both locally and nationally is very closely linked with the continued financial health of the consumer.

Increasing business investment and/ or improving the trade balance would balance the economy but it will not be implemented in the short-term. In addition, although the UK Government has pushed back its target date for a balanced budget from 2020/21 to 2025/26, it is not obvious that a large fiscal stimulus, either through increased spending or lower taxes, would be implemented if consumer spending started to contract. Although it is too early to speculate, one potential consequence of the June 2017 General Election may be a further easing of austerity.

Real income growth is vital

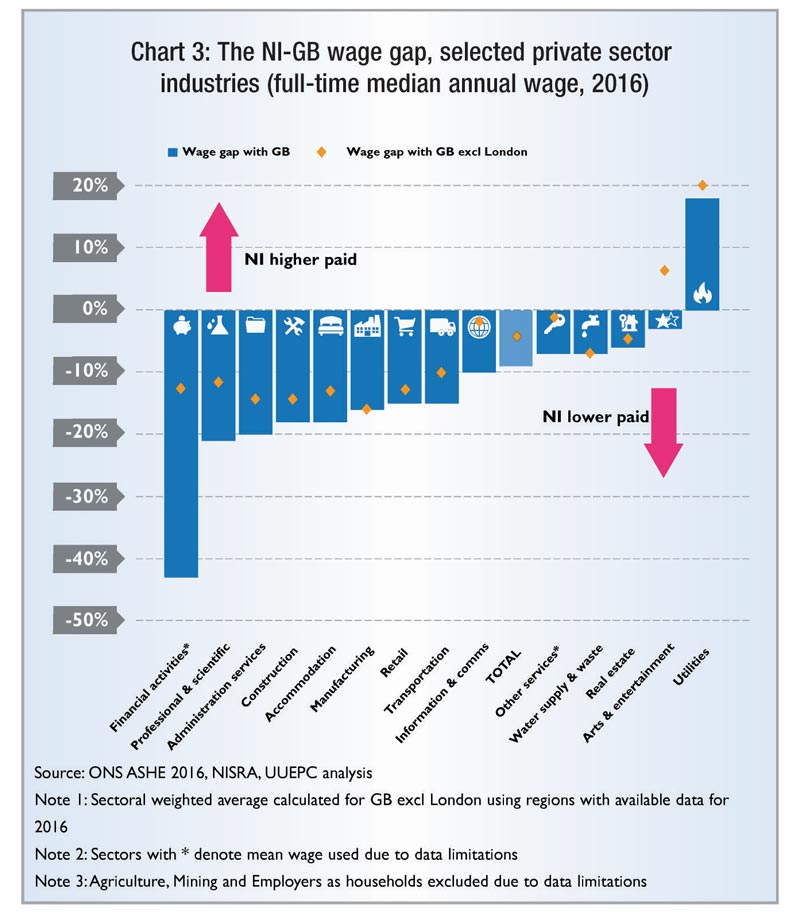

The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) March 2017 outlook forecasts wage growth marginally above inflation (see Chart 2), indicating real wage growth increasing over the next five years. The UUEPC also anticipates similar nominal wage increases but crucially we forecast higher inflation, thus eroding real wage growth.

The case for nominal wage growth is strong: the labour market is tightening; there are reported skills shortages across a range of sectors; fears of future immigration controls reducing the future supply of labour; and increased wage demands on the back of higher inflation.

However many of these factors have existed for some time, for example, the UK employment rate is at records levels (74.9 per cent) and unemployment is at a 42 year low of 4.5 per cent. Yet, despite these labour market conditions, earnings growth has been subdued and this is confirmed in the latest Bank of England Agents Report (May 2017) which found that pay awards “remain clustered around 2 per cent-2.5 per cent across the economy”. Therefore, there is no immediate evidence that incomes will start to increase at a faster pace.

In the short term, the OBR forecasts public sector pay restraint will remain with nominal increases of approximately 1.5 per cent p.a. out to 2019. This is below the projected level of inflation, indicating that real income squeezes are in store for public sector workers. Near zero nominal increases in earnings are not welcome, but are tolerable when inflation is very low, however with inflation above 2.5 per cent and several years of pay restraint in the recent past, industrial tensions are likely to rise.

Added to the political pressure of Brexit, maintaining public sector pay restraint will be a challenge over the next Westminster parliamentary period. It is therefore unsurprising that even some Cabinet ministers are suggesting a re-think on public sector pay should be considered.

The changing nature of employment in Northern Ireland

Understanding the reasons for low earnings growth is critical to developing appropriate policy responses. In the first instance, labour market weaknesses exist including significant ‘underemployment’ (i.e. where people work fewer hours than they would like or at a level below which they are qualified to work). Since 2012, part-time employment has been growing at a faster pace than full-time employment (8 per cent P/T compared to 6 per cent FT).

In addition, there has been a significant increase in self-employment, which can be seen as positive in terms of increased levels of entrepreneurialism but the greatest level of growth has been seen in part-time self-employment (12,000 compared to just 5,000 additional full-time self-employed).

This may suggest a growth in the gig economy which is attractive to employers as it reduces the need to make employers National Insurance and pension contributions, but it is typically low paid.

This changing nature of employment suggests that despite record high levels of employment, there may be greater additional supply in the labour market than the headline figures may suggest. As a result, there could be significant scope for further labour market tightening before pressure to increase earnings picks up.

Does the Northern Ireland wage gap matter?

Economic forecasts tend to focus primarily on GDP. This is an important measure for determining change in economic activity and comparing performance across different economies. However, it is an imperfect measure at a regional level. As a result, the UUEPC also focuses on labour market performance across sectors and wage analyses to obtain a better understanding of overall living standards and economic activity.

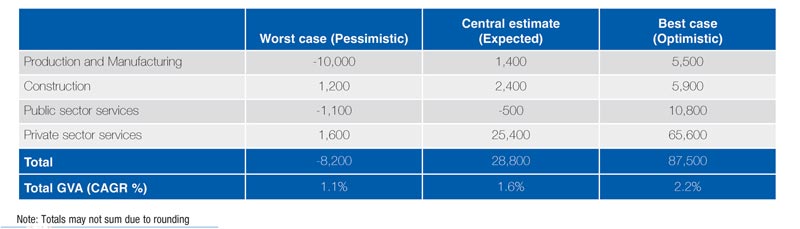

The average full time wage in Northern Ireland is £26,070 compared to £28,560 across Great Britain (GB) as a whole, resulting in a wage gap of 8.7 per cent. At the headline level this is quite significant, however, removing London from the analysis, given its lack of comparability with the local economy, the gap reduces to only 3.6 per cent.

Taking a more detailed sectoral view, some interesting patterns emerge (see Chart 3). For example, the financial sub-sector has much lower average earnings than other GB regions, but, removing London from the analysis reduces the gap from 43 per cent to 13 per cent. HM Treasury analysis has shown a strong link between productivity and wages and therefore a desire to see higher wages requires an increase in productivity.

In general, lower wages in Northern Ireland are often explained by lower levels of productivity due to a higher concentration of lower productivity sectors, such as agriculture, and a greater focus on lower value-added activities within individual sectors, such as financial services.

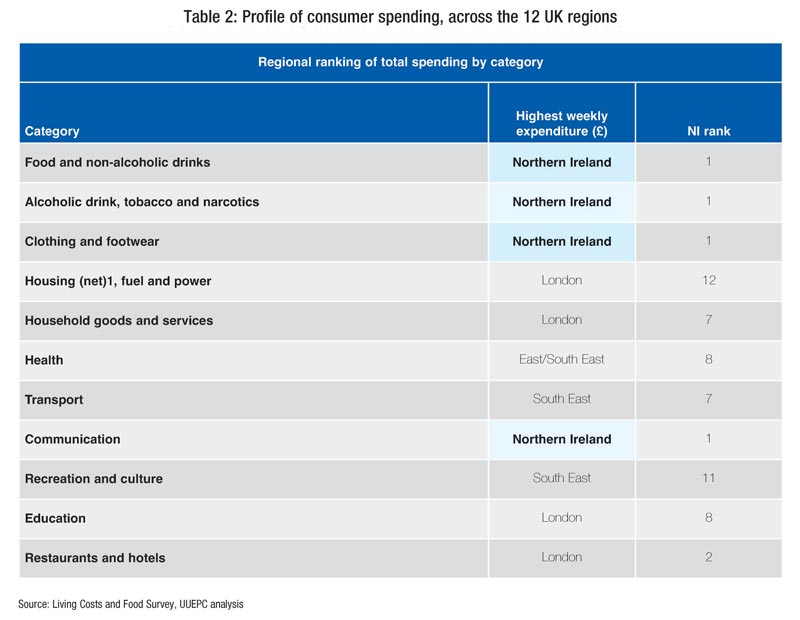

Understanding if this income gap matters at the individual level is more nuanced than first appears. An ambition to increase earnings to a level closer to the UK average is appropriate, but it is also important to reflect the overall cost of living. A significant portion of overall household spending is allocated to housing, which in Northern Ireland is only 12 per cent compared to 22 per cent in the UK as a whole. The impact of lower housing costs1 along with the “super parity” issue (i.e. people from Northern Ireland pay lower taxes/ public sector charges than those in GB on similar incomes, such as domestic water charges, prescription charges, tuition fees and public transport), has resulted in local households having different spending patterns compared to the rest of the UK (see Table 2).

As a proportion of overall spending, Northern Ireland households spend least on housing and most on food, alcoholic drinks, clothing and communications relative to other UK regions. Northern Ireland is also second only to London in hospitality (restaurants and hotels) expenditure.

Given the different weightings of expenditure across the regions, uniform price changes in goods across the UK has a different impact in each region. The UUEPC research has indicated that Northern Ireland has faced relatively weaker price pressures compared to other parts of the UK. For example, a representative basket of household expenditure in Northern Ireland costs 1.0 per cent more in 2016 relative to 2013, whereas in London a representative basket costs 2.5 per cent more over the same period.

Northern Ireland’s weaker price pressures has been driven by a number of factors including items such as transport and clothing, which make up a greater share of Northern Ireland spending. This has been a good news story in recent years, but if the cost of clothing or oil were to increase significantly in next few years, it would have a proportionately greater impact on Northern Ireland consumers. This is now more likely given the depreciation of sterling.

The UUEPC has completed research on Northern Ireland consumer spending and incomes patterns compared to other UK regions, which was published last month.

Sectoral outlook

Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector has enjoyed four years of strong growth since the trough of the recession in 2012. The sector has created 10,300 jobs, equivalent to 13 per cent growth and has been the fastest growing sector of the Northern Ireland economy. This is in contrast to manufacturing in the rest of the UK which has grown by only 2 per cent over the same period.

The overall outlook remains positive as some of Northern Ireland’s main export markets, including the EU, are posting stronger economic growth and sterling depreciation improves price competitiveness. However, employment growth is likely to stall because of the high profile closure and redundancy announcements at JTI, Michelin, Bombardier, Shrader and Caterpillar which will be largely implemented in 2017/18.

Based on average manufacturing productivity levels, a contraction of 3,000 jobs (approximately equivalent to the announced closures listed above) would reduce overall Northern Ireland GVA by approximately 0.5 per cent. This is a key driver in the reduced level of Northern Ireland GVA growth in the UUEPC 2017 forecast.

Construction

The construction sector in Northern Ireland has been severely impacted since the economic downturn, with employment levels still 34 per cent below the 2007 peak. Since 2013, the sector has experienced a gradual recovery creating nearly 2,000 jobs (3.4 per cent increase). Encouragingly, as measured by the Northern Ireland Construction Output, 2016 ended positively with output volumes increasing by 12.8 per cent over the year. This is the highest level of output growth reported in the last five years.

The outlook for the sector is mixed. Residential development should be positive as historic supply constraints provide a basis for continued modest growth in prices. In addition, commercial development, particularly in the hospitality and office sub-sectors, are also experiencing an increase in activity. However, the political stalemate at Stormont could result in delays to public sector infrastructure projects.

Private sector services

Private sector services continue to be the most important component of the overall economy in Northern Ireland accounting for two in every three jobs created since 2012. There is an encouragingly broad distribution of jobs created across the services sector, including higher value adding sub-sectors such as ICT and professional services. However, the growth in consumer spending discussed elsewhere in this outlook has not translated into increased employment in the retail sector as it strives to improve productivity.

Looking forward, short-term sentiment indicators such as the Purchasing Managers Index and consumer confidence measures are positive and in the longer-term, the UUEPC forecasts suggest that private sector services will continue to be the leading driver of job creation in the economy, creating 25,000 jobs over the next 10 years.

Public sector services

Employment levels across the public sector as a whole have been broadly flat, increasing by just 6,800 since 2012 (a rise of just 2.6 per cent). The health sector has seen its budget protected as it deals with a range of challenges including the increased demands of an aging population. As a result, employment levels in the health sector continues to increase. Employment in education has experienced moderate expansion but public administration has continued to see employment levels contract.

The process of re-balancing the economy from the public sector to the private sector is taking place partially due to government spending constraints and employment growth being restricted to the private sector.

Looking forward, although the budget outlooks are unclear, the UUEPC has assumed that the next UK Government will maintain a constraint on fiscal spending. However, it is recognised that the UK General Election result could see a brake applied to austerity, which would increase the number of public sector jobs.

W: www.business.ulster.ac.uk/epc/

E: economicpolicycentre@ulster.ac.uk

T: 028 9036 6561

Twitter: @UlsterUniEPC