Post-Brexit immigration laws

A central tenet of pro-Brexit arguments, the UK Government has rolled out its vision for post-Brexit immigration, signalling its preference for a much more restrictive points-based system. The suitability of the uniform proposals, especially in Northern Ireland, has since come under question.

Following the publication of the Migration Advisory Committee’s (MAC) report on salary thresholds and points-based systems, the Government released a policy statement detailing its plans for the future of UK immigration, outlining its intention to “attract the high-skilled workers we need to contribute to our economy, our communities and our public services” and to create a “high wage, high skill, high productivity economy”.

The new rules will take effect from 1 January 2021 and the UK Government says that they “recognise that these proposals represent significant change for employers” and that they will deliver a “comprehensive programme of communication and engagement” in the meantime, and thereafter “keep market data under careful scrutiny” to monitor pressure zones in key sectors.

These reforms, the Government says, will eventually lead to “further improvements” in the UK’s sponsorship system and the operation of the UK border, which will include the eventual introduction of Electronic Travel Authorities. Throughout the process of developing these rules, the Government has accepted the MAC’s recommendations to lower both the general salary and skills thresholds, from £30,000 per annum to £25,600 and from RQF6 (bachelor’s degree) to RQF3 (A Levels or equivalent).

Points-based system

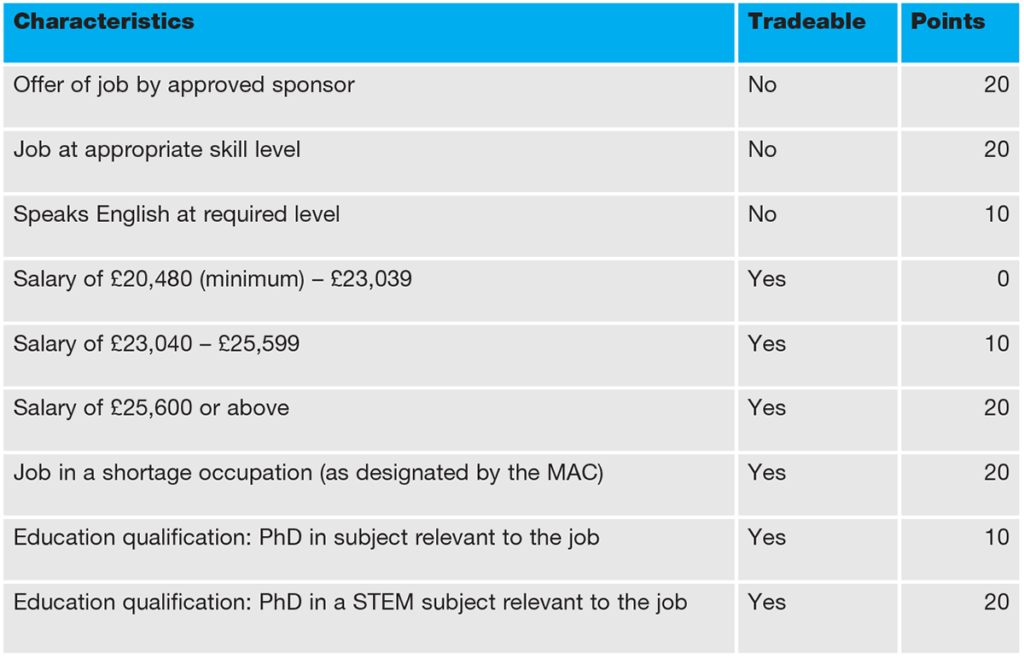

Every applicant will be required to meet a threshold of 70 points in the new points-based system in order to obtain a visa. Core to these points are three criteria: a job offer (worth 20 points), the job offer being at an “appropriate” skill level (20 points) and the applicant possessing English language proficiency to a desired level (10 points).

While some point qualifiers are tradeable, allowing the applicants to juggle conditions in order to make up the required 70 points, the above three are not in most situations.

For example, an applicant meeting the three criteria above that is offered a job on or above the general salary threshold of £25,6000 per annum will be awarded 20 points, and thus the full 70, for that salary level. However, someone offered a job within the minimum allowable salary threshold (£20,480-23,039, worth 0 points) could make up that shortfall by possessing a PhD in a STEM subject relevant to their job (20 points, 10 points for non-STEM subjects) or by being offered a post in a MAC designated shortage occupation (20 points).

The MAC will produce and maintain a shortage occupation list that will decide which occupations will give applicants that 20-point boost in order to provide “immediate temporary relief for shortage areas”. The UK’s current shortage occupation list contains a wide array of professions, from teachers to the creative arts, but shortages are at their most prevalent in the STEM and medical professions. “As now,” the Government says, these workers will be able to be accompanied by their dependents.

The Global Talent route that previously applied to non-EU citizens will begin to apply to EU citizens, meaning “highly-skilled” workers who can achieve the required level of points will be allowed to enter the UK without a job offer if they are endorsed by a “relevant and competent body”. There will also be a “broader unsponsored route” in line with MAC recommendations. Proposals for this route will be explored in the “coming year”. In May, after the Government’s plans had been published, Parliament voted to give initial backing to legislation that would end free movement of workers between the UK and the EU.

Northern Ireland

It remains to be seen how these new rules will impact Northern Ireland, but initial reaction across the political spectrum has been largely negative, ranging from outright condemnation to queries as to whether regional variability, as yet unannounced, will be possible.

Sinn Féin MP Chris Hazzard called the policy statement an “unworkable proposal that is going to cause havoc for our local economy”, a view repeated by SDLP MP Colum Eastwood and UUP MLA John Stewart, who respectively called the statement a “fundamental threat” and an “absolute disaster for the care sector in particular”.

Alliance MP Stephen Farry commented on the uniformity of the proposals, saying that a “one-size fits all approach doesn’t work”, while DUP MP Jeffrey Donaldson said that there are “different needs in different parts of the UK and we have the agri-food sector as our biggest industry here”.

Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate fell to 2.4 per cent during quarter four of 2019, but the rate of economic inactivity (25.6 per cent) is significantly higher than Britain’s (20.6 per cent). Economic inactivity is collated in part using the amount of students, sick, disabled and retired people within an area, and while some of these are expected to enter or return to the workforce, it is projected that this amount will not make up the labour shortfall these new rules will create in Northern Ireland.

The uniformity of the measures is something that does not give recognition to the economic disparity present within the area covered by the rules. Average weekly earnings in Northern Ireland are £535, £50 lower than the UK average of £585. Northern Ireland has experienced better year-on-year growth in that area (3.3 per cent nominal and 1.2 per cent real growth versus the UK’s 2.9 per cent nominal and 0.9 per cent real) but that simply serves to illustrate the historical gap that has existed between the earnings in Northern Ireland and in the rest of the UK. The median yearly income in Northern Ireland is £22,491, rising to £27,434 for full-time workers; in the UK as a whole, these figures are £24,897 and £30,353 respectively. The full-time mean is £32,083 in Northern Ireland and £37,428 in the UK.

Even in terms of specified shortage occupations, Northern Ireland is at a deficit. For example, a registered nurse in Northern Ireland can earn between £17,000-35,000, with a median salary of £23,337. Northern Ireland has a lower floor, ceiling and median than London (£21,000-37,000, median of £26,205) and Glasgow (£22,000-36,000, median of £25,594) and a lower floor and median but higher ceiling than Bristol (£21,000-30,000, median of £25,965). Of these four areas, it is only possible in Northern Ireland to earn less than the absolute minimum allowed for applicants in what is a critical shortage area.

It is the salary thresholds that seem to pose the greatest threat to Northern Ireland, with it not being unusual for professionals such as architects and solicitors to earn less than the £25,600 threshold here. There are fears for shortages in agriculture also, where plans to expand the number of seasonal workers allowed to 10,000 have been dismissed as not being nearly enough. So much of Northern Ireland’s industry works on an all-island basis, especially the food and drink sector, whose base supplier is agriculture.

With 65 per cent of migrant workers in Northern Ireland being EU citizens, compared to 40 per cent across the UK, this raises the prospect of industry simply moving south of the border to maintain this labour supply. The MAC has estimated that 70 per cent of the EU migrants who have entered the UK since 2004 would not be eligible for entry under these new rules, which would impact industry here more than anywhere else. This reform has been one of the strongest propellers for pro-Brexit arguments and Brexit certainly means Brexit; what that means for Northern Ireland looks bleak.