Robotic Process Automation: threat or opportunity?

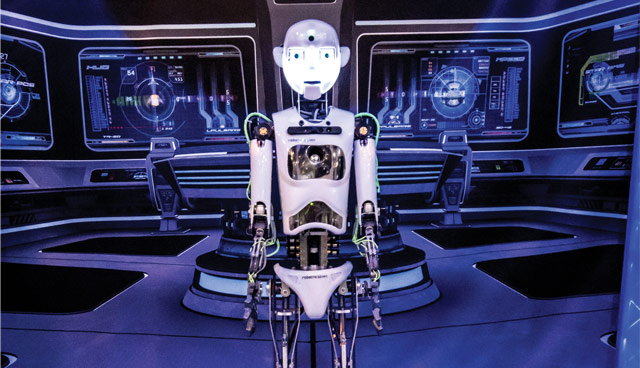

The robots are coming. But it’s ok. It’s not quite in the shape of a dystopian future that Hollywood would have us believe is around the corner. No need to send Arnie back to save us just yet, writes Andy Hughes, Equiniti ICS.

Automation of the workplace isn’t new. Society has previously faced the robotics challenge in manufacturing. Long gone are the days of having your car screwed together in UK centric car plants by swathes of workers, replaced instead by the automated, robotic production lines we see across Nissan and JLR plants in Sunderland and Liverpool. The manufacturing landscape has changed beyond all recognition over the last 40 years, yet, in late 2018 we witnessed the lowest unemployment rate across the UK in 44 years. Clearly something has changed, but not for the worse.

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) is looking to do with the digital industry what robotics has done successfully for manufacturing. Like robotics, RPA is highly disruptive. It looks to take manual tasks completed by employees on digital platforms and automate them. Deloitte defines RPA as “a virtual workforce” that uses software “to capture and interpret existing IT applications to enable transaction processing, data manipulation and communication across multiple IT systems”.

Before we all run off in panic that we’re going to be replaced by robots, it’s important to understand what RPA does and doesn’t do well. RPA on its own, is dumb. It can pick up manual, repetitive tasks and perform them 20 times faster than you or I. This becomes massively powerful when you think of it in the context of legacy applications, which rely on physical data input with little to no interfaces to other digital platforms. Highly workflowed or interfaced solutions are also prime candidates. Where previously organisations needed to invest in API or database layer interfaces to create a highly complex digital landscape, there is a compelling argument to introduce cost-effective robots in the short to medium term. They provide a tangible and shorter process completion solely by reducing the amount of time needed to complete processes.

RPA doesn’t, however, improve your process. A bad process remains a bad process, RPA will just do it quicker. You still need employees and experts to tell you what your process is and how to make it better. Ask yourself, does your organisation embrace continuous improvement? If the answer is “no” or “we don’t have the time or resource to improve it”, well then there is good news. RPA is here to enable your employees to concentrate on improving your business. Making your processes more efficient, engaging with your clients and citizens, making decisions and providing an excellent service.

Streamlining will play a key part in the digital robotics revolution we’re about to experience, just like it did in the manufacturing industry. The trick is for the public and private sector to lead the way in embracing it. Let’s show how it can change our organisations, using our employees to improve our business, not just type into spreadsheets all day.

I mentioned earlier that RPA is dumb. What I didn’t mention, is that if we merge the rising stream of artificial intelligence (AI) into RPA, exciting, world changing things are going to happen. A story for another day, but maybe we do need Arnie after all…

Contact

Equiniti ICS

T: 028 9045 4166

E: enquiries@equiniti-ics.com

W: www.equiniti-technology.com