Poverty in Northern Ireland

There was a slight fall in relative poverty between 2022/23 and 2023/24 according to data from the Northern Ireland Poverty and Income Inequality report 2023/24, published by the Department for Communities (DfC) in March 2025.

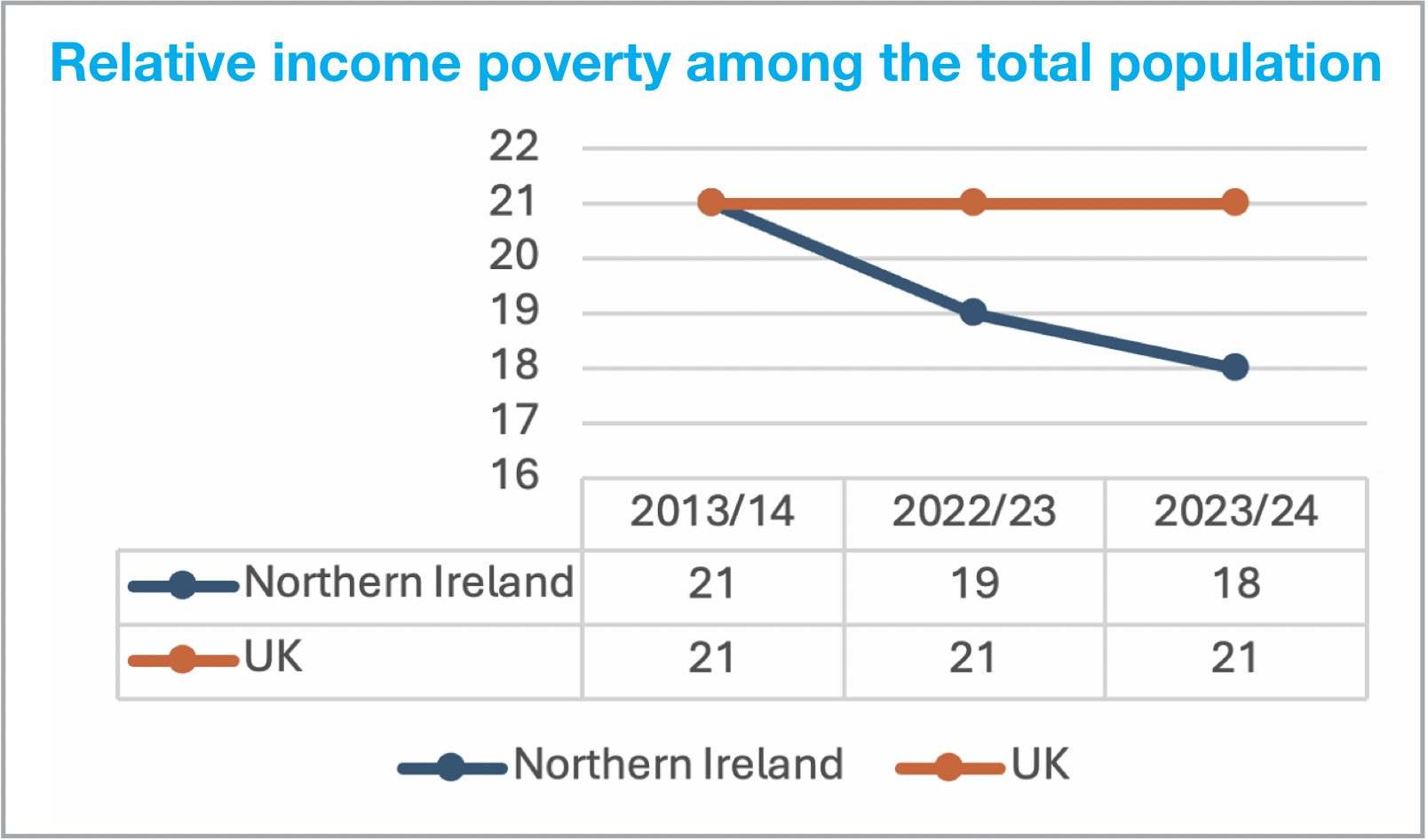

In 2023/24, approximately 335,000 people (18 per cent of the total population of Northern Ireland) were in relative income poverty. Relative poverty is where a household has income of less than 60 per cent of the UK median household income.

After housing costs, the median income for households in UK ranges from £17,058 for single people without children, and £47,645 for couples with children. The relative poverty threshold in the UK in 2023/24 ranged from £10,235, to £17,646.

For relative income poverty in the total population, Northern Ireland was below the UK-wide rate of 21 per cent. Northern Ireland experienced a decrease in the rate from 2022/23 when it was 19 per cent (351,000), while the UK rate remained the same. Overall, relative income poverty in Northern Ireland among the total population has decreased from 2013/14 when it stood at 21 per cent (386,000), in line with the UK rate that year.

Data also shows the rate of absolute income poverty in Northern Ireland – households whose equivalised income is less than 60 per cent of the inflation – adjusted median UK household income in 2010/11. The absolute poverty threshold in the UK in 2023/24 ranged from £9,581 to £26,761.

Approximately 279,000 people representing 15 per cent of the total population in Northern Ireland were in absolute income poverty after housing costs in 2023/24, below the UK rate of 18 per cent. This represents an increase from 2022/23 for Northern Ireland when it stood at 14 per cent (271,000).

Children

Of the population of children in Northern Ireland, 25 per cent (115,000) were in relative income poverty in 2023/24, below the UK rate of 31 per cent. This rate remained unchanged for Northern Ireland from 2022/23 while the UK rate increased slightly from 30 per cent. Overall, relative income poverty in Northern Ireland among children has decreased slightly from 2013/14 when it stood at 26 per cent (115,000).

Of the population of children in Northern Ireland, 21 per cent (95,000) were in absolute income poverty in 2023/24, below the UK rate of 26 per cent. This represents an increase for Northern Ireland from 2022/23 when it stood at 20 per cent (93,000).

To tackle child poverty in the UK, groups like Barnardo’s, Save the Children UK, and the Child Poverty Action Group have put pressure on UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer MP to scrap the two-child benefit cap. Introduced by Tory former chancellor George Osborne, the cap prevents parents from claiming benefits for any third or subsequent children born after April 2017.

The Child Poverty Action group said: “In the absence of government intervention, the number of children in poverty in the UK is expected to rise from 4.5 million to 4.8 million by the end of this parliament.”

Working-age adults

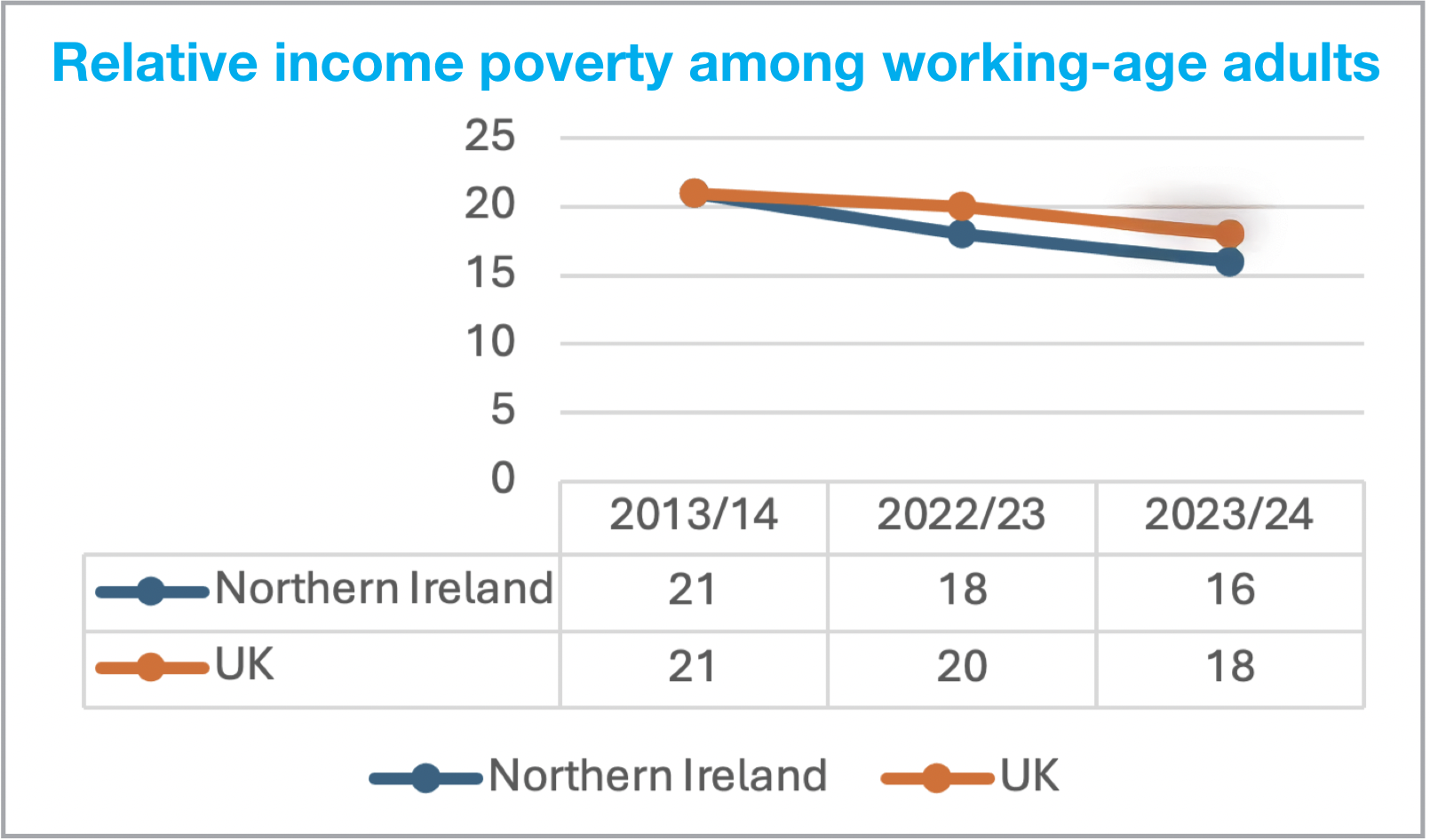

Approximately 16 per cent (185,000) of working-age adults in Northern Ireland were in relative income poverty in 2023/24, below the UK rate of 19 per cent. This represents a decrease from 2022/23 when it stood at 18 percent, while the UK rate also fell from 20 per cent. Overall, relative income poverty in Northern Ireland has decreased from 2013/14 when it stood at 21 per cent (225,000), in line with the UK rate that year.

For working-age adults, 14 per cent (157,000) were in absolute income poverty, below the UK rate of 17 per cent. This figure remained unchanged from 2022/23 for Northern Ireland.

Pensioners

For pensioners, 12 per cent (35,000) were in relative income poverty in 2023/24, below the UK rate of 16 per cent. This rate remained unchanged for Northern Ireland and the UK from 2022/23. Overall, relative income poverty in Northern Ireland has decreased from 2013/2014 when it stood at 16 per cent (46,000).

Approximately, 27,000 pensioners in Northern Ireland representing 9 per cent were in absolute income poverty, below the UK rate of 13 per cent. This represents an increase for Northern Ireland from 2022/23 when it was 7 per cent.

In July 2024, a decision was taken to means test the Winter Fuel Payment (WFP) which DfC estimates would impact 250,000 pensioners. To mitigate this, Communities Minister Gordon Lyons allocated £17 million from the Executive to provide one-off fuel support payments of £100 for people no longer eligible for WFP.

Anti-Poverty Strategy

DfC aims to tackle poverty through the Anti-Poverty Strategy, which was signed off by Executive members in May 2025. In March 2025, the Royal Courts of Justice found the Executive Committee in breach of its legal obligation to adopt the Strategy, a requirement under the Northern Ireland (St Andrews Agreement) Act 2006.

A DfC spokesperson tells agendaNi: “Poverty is a complex and multifaceted issue with many different root causes and effects. Poverty impacts every aspect of society and effectively tackling this issue will lead to benefits, not only for individuals and families but for the wider community and economy.”

“The Northern Ireland Executive Anti-Poverty Strategy will aim to reduce the risk of falling into poverty, mitigate impacts and support people in exiting poverty. It will set out a cross-departmental commitment to a joined-up, long-term approach to addressing poverty across all ages.”