CASE: Helping put Northern Ireland’s sustainable energy sector on the map

Samantha McCloskey of Northern Ireland’s Centre for Advanced Sustainable Energy discusses the centre’s work on energy from biomass; energy systems and turbines.

The tremendous scale of the success achieved by CASE (Centre for Advanced Sustainable Energy) over the past four years was profiled by the organisation’s Director Samantha McCloskey, courtesy of her presentation to the recent Energy Ireland conference.

She attributed the development of this ‘good news story’ to the partnership obligation, which requires CASE to work with commercial businesses in order to evolve technological research solutions, where sustainable energy is concerned.

According to McCloskey, CASE draws its research expertise from three centres of excellence: Queen’s University Belfast, Ulster University and the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI).

The organisation was established in 2013 with funding made available through the Invest Northern Ireland Competence Centre programme in order to drive collaborative Research and Development (R&D) in sustainable energy. Three key research themes have been identified for CASE: Energy from biomass; energy systems; and turbines.

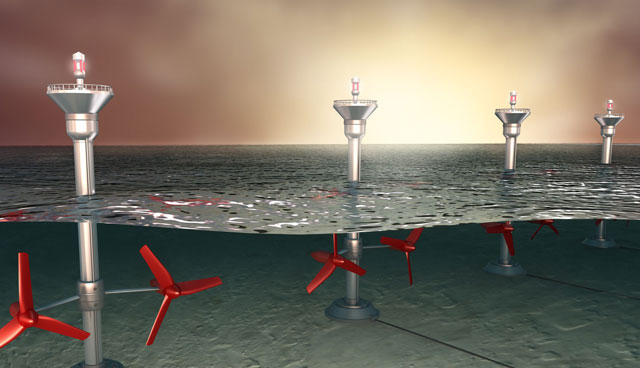

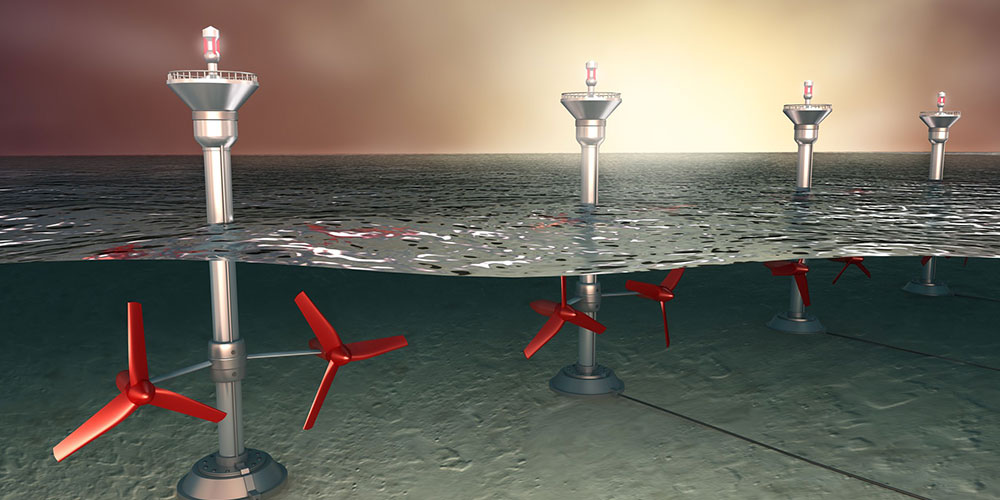

McCloskey confirmed that CASE and a number of commercial partners – including McLaughlin & Harvey and Oceanflow – have collaborated in developing ocean turbines that break new ground in helping to harness the immense energy contained within day-to-day tidal movements.

“This work has highlighted the unique value of Strangford Lough as a location to trial ocean turbines. We have received requests from research institutions in countries around the world, seeking our collaboration on a range of turbine projects, currently at various stages of development.

“To date £1 million of our initial £5 million research fund has been used to pump prime the work at Strangford to develop ocean turbines that will work under commercial conditions.

“Christened Tandem Tidal Turbines, or Triple T, the second stage of the project has provided us with a valuable opportunity to thoroughly analyse the raw data coming from the test turbines.”

According to McCloskey, the Triple T project was conceived to investigate the effect of scale on commercial turbine performance, compared to modelling options. It will also quantify the difference between turbine blades used in wind and tidal applications, while also determining the effect of turbulence and wave action on device performance.

Allied to all of this has been a series of exhaustive studies on mammal behaviour as animals interact with the turbines now operational in Strangford Lough.

McCloskey confirmed that strategic research will be required to allow Northern Ireland to develop the low carbon technologies needed to make sustainable energy a meaningful reality moving forward.

Turning to biomass-related research carried out under the auspices of CASE, McCloskey highlighted the development of organic pellets, made from the digestate produced by anaerobic digestion plants. The project aims to produce hard, dry and environmentally stable granules for a range of possible industries.

“This work has been carried out by AFBI. The pellets have been assessed for their calorific value and as slow-release fertilisers,” said McCloskey.

“Courtesy of our SUBB programme, we are assessing potential sources of biomass produced here in Northern Ireland. These include poor quality forest residues, waste woods, oversized compost materials and a range of agricultural residues.

“Land management operations also produce a range of biomass materials including branches, reeds, rushes and scrub,” she added.

“We have recently partnered with the RSPB to assess the biomass potential of the materials dredged form the many ponds under their control.”

The development of new biofuels is proving to be a fruitful area of research for CASE.

“An R&D team, involving representatives from Queen’s University Belfast, has developed a new dual fuel which is helping to produce savings of up to 27 per cent, when compared to the costs incurred using diesel only,” said McCloskey.

“These results have been confirmed courtesy of a trial involving a 50 tonne lorry and milk tanker with a 350km daily collection route.

“On the basis of 2016 fuel prices, this works out a saving of £40 per day.”

Turning to research which has facilitated the development of new energy utilisation systems, McCloskey profiled the use of intelligent technologies with a focus on off-grid solutions. A case in point is the development of the Coleraine Micro-Grid.

This will see Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council investigating the development of a micro-grid, built for and developed to create more energy within its catchment area. The aims include addressing the shortcomings in grid distribution, developing a means of supplying cheaper electricity and decreasing distribution cost while, at the same time, increasing distribution efficiency.

McCloskey confirmed that CASE will be seeking funding to allow it to facilitate additional research over a further three-year period.

“We are also committed to securing relationships with international partners during the period ahead.

“It is also important to learn from the lessons of the past. A key issue to be addressed is that of balancing the academic aspects to specific research projects with the practical targets set by our commercial partners.

“Contractual negotiations can also get in the way, as can too many managers, especially if a large consortium is involved.

“On the positive side, we are delivering a number of bespoke solutions that will generate new jobs and export opportunities for local businesses.”

McCloskey confirmed that CASE had engaged with 48 companies across 18 projects over the past four years.

“We have managed to get £5.56 million of external, leveraged funding from sources as diverse as Horizon 2020, Innovate UK and Interreg.

“Our mid-term review has highlighted the genuine benefits that CASE brings to bear. Up to this point £4.96 million of Invest NI funding has been allocated.”

According to McCloskey, competence centres – such as CASE – offer commercial companies an opportunity to develop new products, processes and services and bring them more quickly to global markets, as well as giving local businesses access to leading edge solutions and skills.

“We were allocated £5 million by Invest NI to be spent over a five-year period on projects that will push forward the boundaries of research into sustainable energy in Northern Ireland.

“This research must have a long-term commercial pay-off. The funding allocated by CASE goes to the academic institutions involved. However, the commercial partners involved will have a major say in how the specific projects are structured and developed.

“Company size has no bearing on the decision by CASE to support a specific proposal. The bottom line is that we are interested in working with businesses, large and small, that have an interest in sustainable energy.”