TRADE UNION DESK: Workers’ rights are good populism

One of the most cynical assumptions in current politics is that the way to the heart of the working class is by appealing to the ascribed and presumed beliefs of people who do not exist. Also that political entrepreneurs who pander to these supposed prejudices are projections of the masses rather than themselves, writes ICTU’s John O’Farrell.

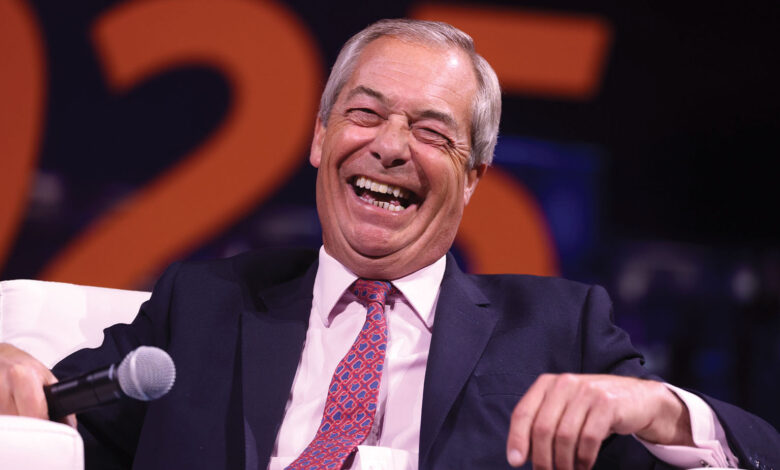

The rise in support in Britain for Reform UK is often and erroneously attributed to ‘the working class’. Naturally, this image of former commodities trader Nigel Farage MP as the workers’ champion is based on a really dumb stereotype of working class people being (1) white and (2) racist.

In fact, ethnic minorities are over-represented in the C2 and D social stratifications. Secondly, surveys of voting trends show that Reform is attracting mostly former Tory voters, with despairing Labour voters from 2024 defecting in greater numbers to the Liberal Democrats and the Greens. Someone should tell Starmer’s strategists.

Noticeably, Reform attracts 35 per cent of male respondents but only 24 per cent of women. What is also striking is age. Over one-third of voters over 50 or over 65 are keen on reform. Fewer than 8 per cent of under 25s like them, thus Farage’s announcement of cutting the minimum wage for the young while keeping pledges on pensions, stamp duty, and inheritance tax.

Another striking thing about Reform, the ‘workers’ party’, is how hostile they are to trade unions and to workers’ rights. By now, the Labour government will have completed all of the stages of its Employment Rights legislation. It should have reached Royal Assent by January 2026, when the Economy Minister Caoimhe Archibald MLA will introduce her ‘Good Jobs’ Employment Bill to the Assembly.

Like the Westminster legislation, the Northern Ireland bill will include workers’ rights already in law or newly minted in the GB Bill, which are very popular with the public. ‘Newspaper of record’ The Times has reflected Rupert Murdoch’s prejudices and has been overwhelmingly negative, but this does not reflect the findings of a YouGov survey it commissioned late last year.

“Populism requires a certain popularity, and being on the wrong side of overwhelming public opinion is no place for any aspiring authoritarian, or even a benign ruler.”

“The Bill will heavily restrict the use of zero hours contracts, with employees having the right to a guaranteed number of hours if they wish. This is in tune with the public, with a YouGov survey for The Times in September finding 68 per cent in favour of banning at least some types of zero hours contracts, against only one in nine (11 per cent) who are opposed to any restrictions on them.

“Two thirds of Britons (65 per cent) also wish to see people’s right to work flexible hours expanded, so should be pleased to see the government is legislating for flexible working to be the default, with an employer having to prove that it is unreasonable for them to be able to reject it.

“Likewise, just over six-in-10 Britons (62 per cent) are supportive of proposals to extend the legal right to sick pay, and to give employees protections against unfair dismissal as soon as they start a job, rather than after two years of employment as is currently the case. In both cases, less than one in five Britons (between 17 and 19 per cent) are opposed to the plans.”

Opinium polling for the TUC showed overwhelming levels of support for better working rights affecting day one protections against unfair dismissal and for sick pay; a ban on ‘fire-and-rehire’ and on zero-hours contracts; and greater support for “giving trade unions a right to access workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of joining a union”.

Naturally, all of Reform’s MPs have opposed these rights. The Tories have pledged to ‘tear up the Employment Rights Act’ should they ever get back into office.

During the anti-European campaigning ahead of Brexit, a common slogan on the right was ‘British Jobs for British Workers’. Those exact same people who got their wish now want those ‘Brexit freedoms’ to deny ‘British rights for British workers’ despite their popularity among voters, especially those of working age.

Populism requires a certain popularity, and being on the wrong side of overwhelming public opinion is no place for any aspiring authoritarian, or even a benign ruler, not least before attaining power.

A recent definition of conservatism is that there are differing groups for whom the law protects but does not bind, or for whom the law binds but does not protect. Most people want to live under a rule of law which protects their rights at home, on the streets and at work. Legislating for such a popular impulse ought not to be that difficult.