Skills: Retention and attraction key

Ambitions to bridge skills gaps in the Northern Ireland economy should not only focus on the retention of skills in the local labour market, but also enhancing Northern Ireland’s attractiveness to skilled labour from elsewhere, a skills audit has found.

Northern Ireland currently has one of the lowest abilities of all UK regions to attract talent, meaning the importance of talent retention is heightened. However, also highlighted in a recent assessment of Northern Ireland’s skills landscape is the importance of increasing the attractiveness of Northern Ireland to enable the importation of skills outside the local labour market.

Described as the largest net loser of high skilled labour amongst UK regions, Northern Ireland faces not only short-term labour pressures, exacerbated by the pandemic, but also long-term strategic challenges to develop and maintain an internationally competitive labour market.

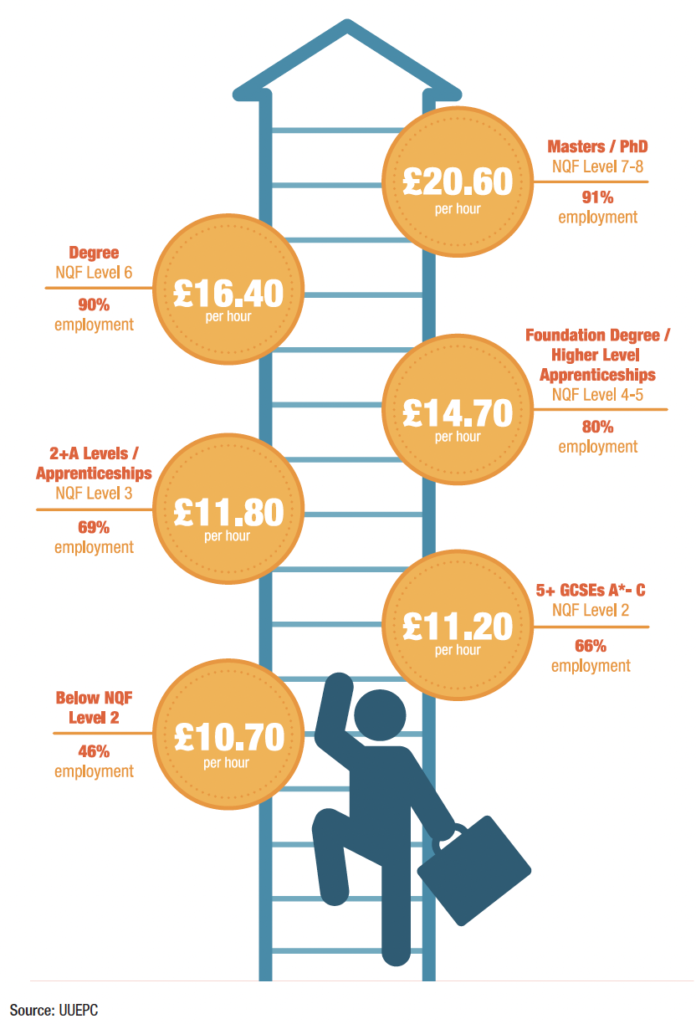

The long-standing prevalence of a ‘missing middle’ in the Northern Ireland economy’s skills supply continues to exist, as evidenced by the Department for the Economy’s latest Skills Barometer, and has in fact been exacerbated by the pandemic. Despite widespread acknowledgement of a changing mix of skill requirements, to address demand for the next decade and beyond, employers’ continued preference for highly qualified individuals continues to squeeze out those with low or no qualifications, as evidenced by an increase of those qualified to degree level or above now accounting for 41 per cent of total hours worked in Q3 2021, up from 32 per cent in Q1 2020.

As a result of employer preference, education attainment in Northern Ireland continues to increase with records showing that almost half (49 per cent) of Northern Ireland school leavers transitioned directly to higher education in 2020.

Challenges to ensuring a skills supply suitable to meet the changing demand of the future are also being impacted by a range of other factors including a reduction in migrant labour availability, and highest levels of early retirement, coupled with economically inactive students, for over a decade.

Increased retention in the education system is reducing the annual flow of qualifiers into the labour market and with a larger number of qualifiers achieving higher level qualifications, the labour supply is reduced for occupations and sectors typically associated with lower levels of graduate employment. However, despite this, there has been little change to the subject profile at higher education, highlighting the need to improve responsiveness to industry demand.

“The overall supply of qualifications in Northern Ireland remains characterised by a ‘missing middle’, with relatively few mid-level skills provided by the education system which directly transition to the labour market,” the barometer states.

On the supply side, in the context of a high economic growth forecast predicting the creation of an additional 75,000 jobs over the decade, underpinned by rapid growth in sectors such as professional services, ICT and advanced manufacturing, future labour shortages are predicted. According to the barometer research, “there is limited scope to rely on catch up in labour market participation to expand the labour supply over the coming decade” and so, maximising labour force participation will be crucial to meet future skill needs.

Northern Ireland’s low ability to attract talent means that replacement demand is key and this is projected to provide a larger quantum of new jobs over the next decade than sector growth. Therefore, addressing changing skills demand will require a significant level of re-skilling and up-skilling of the current labour force. This challenge is not helped by Northern Ireland’s underperformance when compared to other UK regions on lifelong learning measures.

“In a tight labour market learning opportunities linked to career progression paths will become important as firms compete for labour, and seek to retain existing talent,” the barometer states.

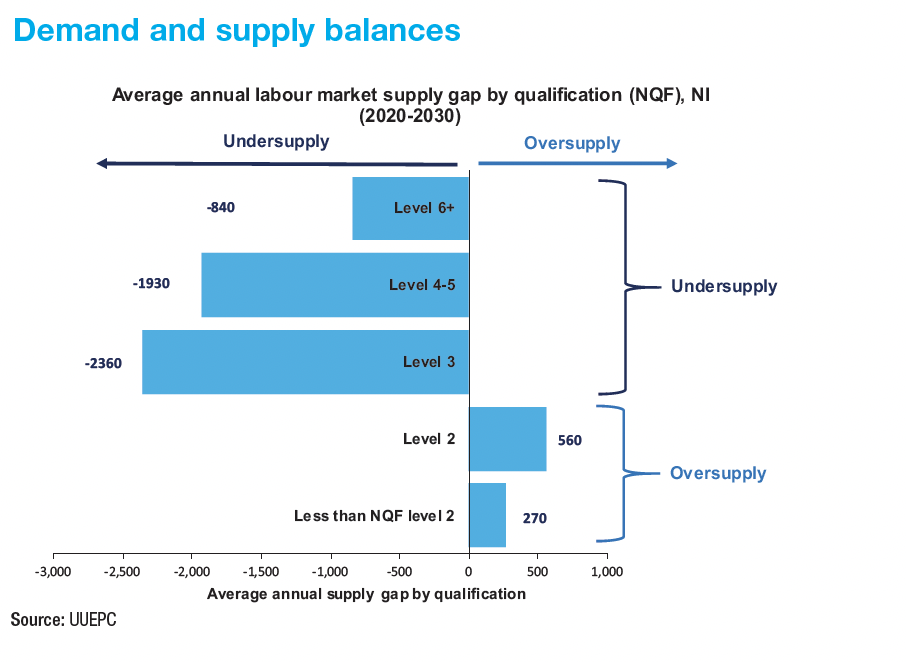

On the supply side, the barometer identifies a slight undersupply of skills at degree level or above (NQF level 6+), but suggests that boosting the transversal skills and increasing work placements for graduates could address this by improving employability. A more significant undersupply exists at mid-level (NQF level three to five), reflecting a relatively small number of qualifiers at that level transitioning to the labour market.

Qualifications of NQF level two and below, classed as low-level qualifications, are slightly oversupplied and will continue to be for the next decade. However, the risk of this flipping to undersupply exists if current pandemic-affected enrolment and attainment patterns, coupled with migration flows, persist.

The barometer also identifies a subject imbalance at higher education level, with a particular undersupply in key narrow STEM subject areas such as computer science and engineering, as well as physical and environmental sciences.

Welcoming the publication of the barometer, Minister for the Economy Gordon Lyons MLA says that the identification of labour supply challenges for the coming decade underpins existing policy objectives such as the creation of a culture of lifelong learning and provides clear evidence of the need to urgently address the digital skills challenge.

Outlining ongoing work between the Department and various stakeholders to “ensure we develop a skills system matched to the needs of a globally competitive small advanced economy”, he adds: “Addressing the skills imbalances is key to driving economic growth and delivering on our societal ambitions. We must ensure people are equipped to meet the changing demands of the labour market now, and in the future, as we strive to become one of the leading small economies of the world.

“I am confident the latest edition of the skills barometer will help people to make career and subject choices and in turn assist businesses as we build the pathway to a 10X economy.”