70 by 30: Renewable electricity project pipeline

Northern Ireland has the potential to almost double its renewable electricity generation in the coming years based on projects already in the development pipeline but the majority of generation capacity is still awaiting construction.

The speed at which renewable electricity generation projects in Northern Ireland pass through the pipeline is significant when considering the Department for the Economy’s ambitious target of 70 per cent electricity generation from renewables by 2030.

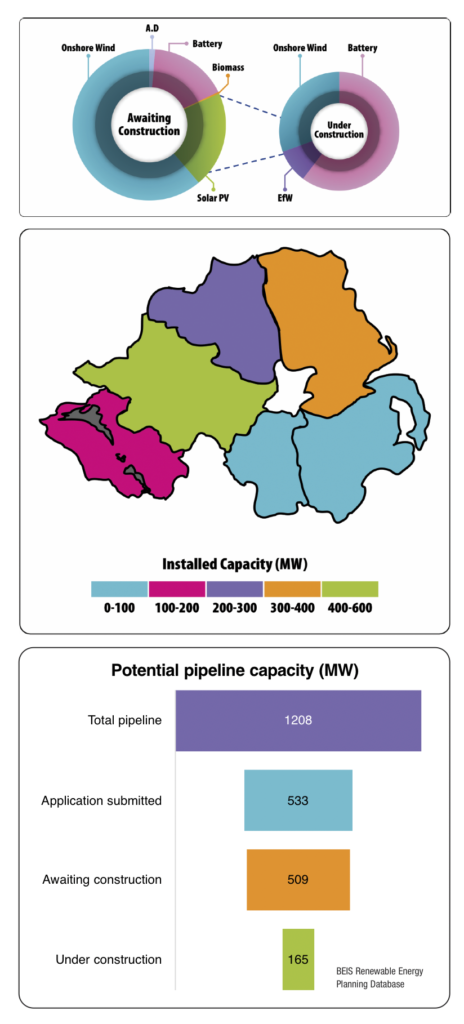

Northern Ireland has a potential renewable electricity pipeline capacity of over 1,208MW, including battery storage, according to the UK’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) database but only 165MW of that capacity had commenced construction by June 2020.

By comparison, 509MW of generation was awaiting the construction phase, where a site has already had planning permission accepted. To offer a context to what the scale of future permitted generation might look like, the 165MW of generation under construction is made up of five sites, ranging in technologies from onshore wind, energy from waste and battery storage.

According to SONI, Northern Ireland has a maximum export capacity of 3,031MW, around 40 per cent of which is installed across renewable electricity sites. Northern Ireland’s two large scale renewable sites are connected to the transmission system, with remaining renewable sites connected to the distribution network.

NIE Networks puts connected generation of renewable technologies at 1,684MW, the majority of which (76 per cent) comes from onshore wind, with solar PV (268MW) a distant second. An insight into the length of time it can take a project to progress through the pipeline from seeking planning approval to eventual generation can be seen by looking at the year 2017, recorded as the largest increase in additional capacity in any given year. Sites commissioned in 2017 generally started construction at least two years prior to generation and some sites’ planning approval dated back to 2007.

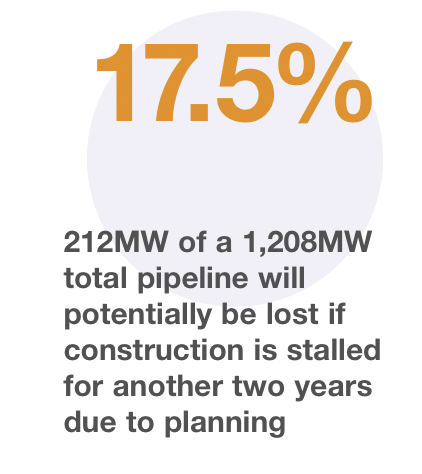

This means that even the 165MW of generation sites under construction will likely not feed into Northern Ireland’s renewable generation for a number of years. Additionally, the Department for the Economy has flagged that of the potential 509MW generation on consented sites which have not begun construction, delay of a further two years would see 212MW of capacity lost due to planning permission timeframes, 17.5 per cent of potential capacity in Northern Ireland’s renewable electricity pipeline.

In terms of location, the majority of Northern Ireland’s current operational capacity is located in the North West, with County Tyrone contributing the largest installed renewable capacity at around 553MW. The majority of this capacity comes from onshore wind and that technology is set to continue to dominate future renewable generation. However, analysis of those sites in the construction phases shows the emergence of greater levels of alternative technologies. A combined 102MW of solar PV generation at three sites is awaiting construction, while planning permission has been granted for Northern Ireland’s largest (39.5MW) solar PV site in County Antrim. Additionally, four storage facilities, with around 184MW of storage potential, exist in the renewable electricity project pipeline. Pipeline capacity includes one marine energy technology. Fair Head tidal site is currently in the planning system for a 100MW development.

Looking to the pipeline, Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council has the largest value of capacity with consented planning permission (141MW), followed closely by Fermanagh and Omagh District Council (129MW). Mid Ulster District Council has significant potential, as it represents 42 per cent of total planning applications currently in the system.

Looking to the pipeline, Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council has the largest value of capacity with consented planning permission (141MW), followed closely by Fermanagh and Omagh District Council (129MW). Mid Ulster District Council has significant potential, as it represents 42 per cent of total planning applications currently in the system.