Project Stratum: Extending broadband coverage in rural Northern Ireland

Nigel Robbins, Broadband Project Director at the Department for the Economy outlines progress on Project Stratum, the £165 million initiative to extend rural broadband.

The Department for the Economy (DfE) will this month publish a report in response to an Open Market Review (OMR) conducted for Project Stratum, which is an initiative to extend broadband connectivity across rural areas of Northern Ireland. The project aims to utilise £150 million allocated through the Confidence and Supply Agreement between the Conservative Party and the DUP. The available funding has increased to £165 million with an additional £15 million allocated to DfE for Project Stratum from the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA).

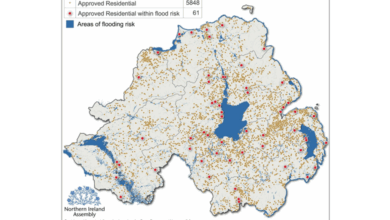

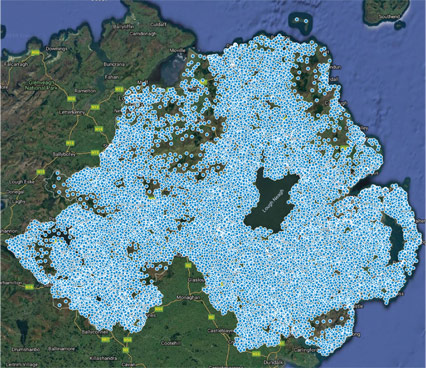

In line with the draft Programme for Government, Project Stratum aims to improve internet connectivity for the 10 per cent of Northern Ireland premises currently unable to access broadband speeds of 30 Mbps or greater – this equates to just under 100,000 premises, across 15,000 postcodes primarily in rural areas, which to date have not benefited from commercial investment.

The Department’s OMR began in 2018, following a period of engagement with the telecoms industry; this was followed by State aid Public Consultation on the OMR’s initial findings, offering citizens and businesses the opportunity to comment on the proposed intervention area for the project. The detailed analysis of over 1,000 responses has now been conducted and publication of the OMR on DfE’s website will be followed by the start of the procurement process for Project Stratum.

The Department has also sought clarifications through Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT) that the funding profile for the project will be in place to deliver such a large scale telecoms intervention. From DfE’s early engagement with the industry, it was clear that a three to four year timeframe would be required to deliver a project of this scale.

The singular aim for Project Stratum is to utilise available funding to improve broadband access infrastructure in Northern Ireland and extend high-speed broadband coverage to as many premises as possible.

The project will benefit from bidders investing in the long-term potential of this future-proofed intervention in predominantly rural areas of Northern Ireland in order to maximise potential coverage. Supplier solutions and models will need to be economically viable under a range of scenarios, though ultimately a bidder’s appetite to invest long-term could potentially secure an essential layer of funding for Project Stratum to extend coverage to as many premises as possible.

A recent shift in UK Government policy indicates that fibre-led interventions are demonstrating better value for money for new public investment, and the majority of premises in the Project Stratum intervention area are likely to benefit from this policy shift. Under the Future Telecoms Infrastructure Review, the UK Government’s ambition is to have full fibre coverage across the UK by 2033. However, State Aid rules require DfE to remain technology neutral within any procurement, and Project Stratum will, therefore, seek to procure solutions that provide at least 30 Mbps to as many premises as possible in the intervention area, through Next Generation Access broadband technologies.

The Department recognises the need for clarity for stakeholders and that is why it has established an NI Broadband Public Project Forum where current project stakeholders, including representatives from DCMS/BDUK, Local Authorities, Ofcom and Project Stratum, can work to ensure that project plans take account of other interventions, eliminate duplication and ensure citizens benefit from broadband interventions as efficiently and cost-effectively as possible.

We look forward to making more detailed announcements about this project in the coming months.