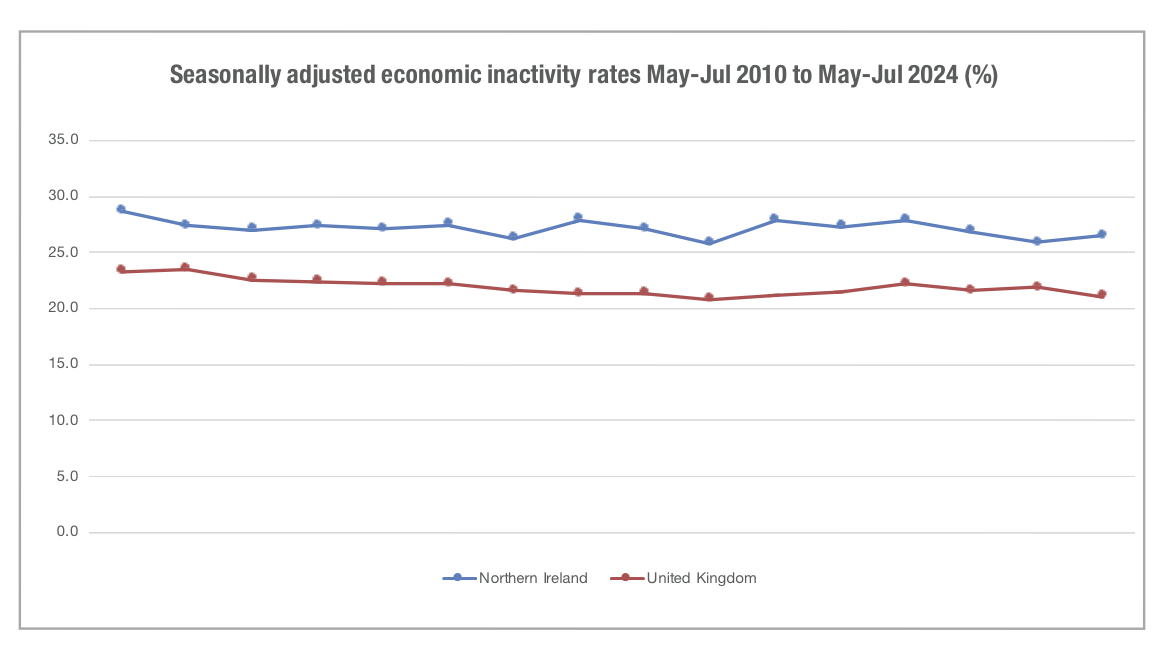

Northern Ireland’s economic inactivity rate has been consistently higher than the UK’s from the period May to July 2010 to May to July 2025, as shown by figures from the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency’s (NISRA) September 2025 Labour Market Report.

The region’s economic inactivity rate – the proportion of people aged 16 to 64 who are not working and not seeking or available to work – stood at 26.5 per cent for May to July 2025, 5.4 per cent above the UK rate of 21.1 per cent.

Although the rate in Northern Ireland has decreased from the previous quarter, it increased by 0.6 per cent over the year. This is slightly below the 0.8 per cent increase recorded in the UK over the year. Economic inactivity peaked in Northern Ireland in late-2010 when it hit 28.8 per cent, compared with the UK high of 23.5 in mid-2011.

A briefing paper on economic inactivity and inclusive labour markets in Belfast and Northern Ireland published by Ulster University in January 2024 states that high rates of economic inactivity “can lead to adverse social and economic consequences”. It asserts that it “restricts the capacity of the economy to grow”, unless it is offset by increases in productivity or immigration.

“A failure to achieve higher rates of labour market participation across Belfast has contributed to a range of personal and broader societal issues, including increased risk of poverty, financial difficulty, loss of human capital, social exclusion, and higher dependence on income replacement benefits,” the report states.

Sickness and disability

Analysis on economic inactivity in the region published by Invest NI in September 2025 attributes Northern Ireland’s high rate of economic inactivity in comparison to the UK to a larger proportion of people out of the workforce due to sickness and/or disability.

Of economically inactive people in the region between April and June 2025, 38 per cent were inactive due to sickness or disability, compared with the UK-wide rate of 31 per cent. This cohort represented 10.1 per cent of Northern Ireland’s population aged 16 to 64, compared with 6.6 per cent in the UK. The number of economically inactive people in the North due to sickness and/or disability has fallen by 2.4 per cent since 2023.

People who do not work due to family and home care commitments represent 19.4 per cent of the economically inactive, while students represent 24.4 per cent. The number of economically inactive people due to family and home care commitments has increased by 10.7 per cent since 2023. The number of economically inactive students has increased by 2.7 per cent. However, Invest NI also notes that economic inactivity in Northern Ireland has been on a general downward trend since June 1999 when it stood at 29.4 per cent.

Furthermore, analysis by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) published in September 2025 asserts: “Those personally exposed to the ‘Troubles’ were significantly more likely to claim DLA later in life, increasing the likelihood by 21 percentage points”, thereby suggesting a generational correlation between economic inactivity and exposure to the conflict, based on historical, long-term analysis.

Additional metrics

NISRA finds that Northern Ireland’s employment rate stood at 71.8 per cent for May to July 2025, a 0.9 per cent decrease over the year. Wages in the 12 months to August 2025 grew by 2.9 per cent (£67) in the region, below the UK’s headline rate of inflation of 3.8 per cent in July 2025.

The number of people on the claimant account in Northern Ireland remained unchanged between July and August 2025, standing at 3.7 per cent of the workforce. Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate for May to July 2025 reached 2.2 per cent, an increase of 0.4 per cent over the year.

Analysis

Mark McAllister, chief executive of the Labour Relations Agency, says: “A slowing down in the labour market seems to be now ‘trending’ as these statistics show what the market has perhaps felt for some time. Despite Northern Ireland bucking the trend on many key statistics in recent times, it was perhaps only a matter of time before we became impacted.”

Identifying redundancies as a bellwether for the economy, McAllister notes that the annual total of proposed redundancies stood at 3,080 for the period of September 2024 to August 2025. This is over 10 per cent higher than the 2,760 recorded the previous year in. He adds that the 12-month totals of proposed and confirmed redundancies “are similar to the levels seen in the decade preceding the [Covid] pandemic”. A total of 2,430 redundancies were confirmed in the period of September 2024 to August 2025.

“In recent times terms like ‘flatlining’ and ‘no growth’ have stalked the business headlines. Is this doom-mongering or prescient predicting? We will have to wait and see,” says McAllister.

Jonathan Simpson, director for employment law at DWF, says: “While economic activity appears to be stalling and we have seen some redundancy announcements, there are also encouraging signs of investment and job creation.

“The local labour market may be struggling to meet job demand. This likely reflects ongoing economic uncertainty, compounded by increased employment costs and the anticipated introduction of enhanced worker protections under the forthcoming ‘Good Jobs’ Employment Rights Bill, which may be prompting some trepidation among employers in some sectors.”

However, Gerry Murphy of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions disputes this assertion, insisting that statistics reflect the “normal churn of employment”.

Murphy adds: “They certainly cannot be attributed to legislation which is presently being drafted and is not due to have its first reading in the Northern Ireland Assembly until the start of 2026. Any slowdown in job creation in recent months cannot fairly be blamed on the proposed Good Jobs Employment Rights Bill.”