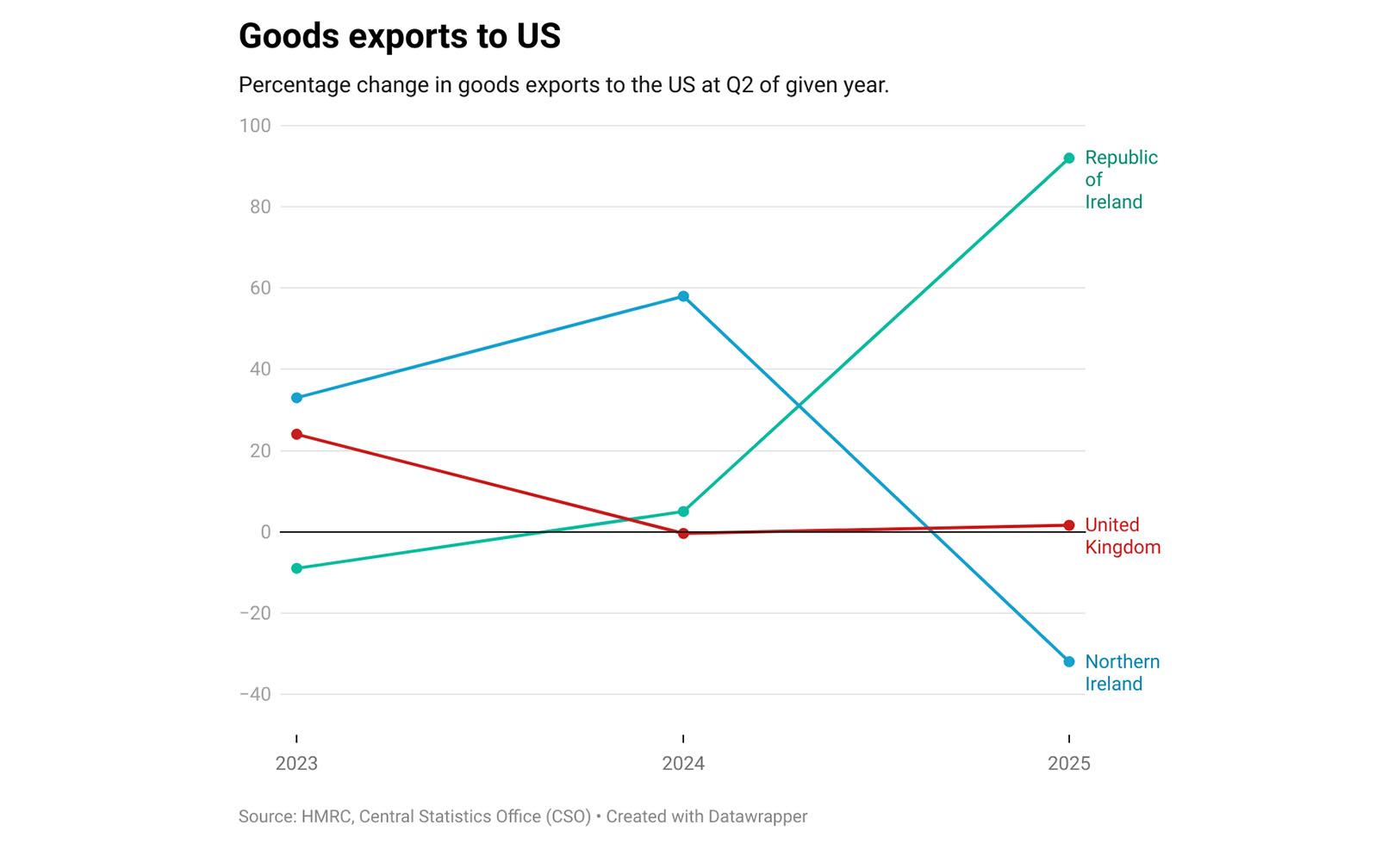

As global economies adapt to the reality of a protectionist White House, Northern Ireland’s exports to the US have dropped by 31 per cent year-on-year, rendering the so-called “competitive advantage” resulting from the tariff border on the island of Ireland meaningless.

Goods exports from Northern Ireland to the US fell by 31 per cent in the year to Q2 2025 compared to the year to Q2 2024 as a mixture of tariffs, global trade uncertainty, and geopolitical strife caused ripples to the Northern Ireland economy. Figures released by HMRC show a year-on-year reduction in exports to the US of £600 million.

Trade with the US is considerable, Northern Ireland exported £1.68 billion in goods to the US in 2024, while importing £752 million from the US in the same period. This represents 15 per cent of all international exports, which totalled £11.1 billion in 2024, a 1.8 per cent increase from 2023 – the only UK region to see such an increase.

In 2024, exports from the Republic of Ireland to the US totalled €72.6 billion – a 35 per cent increase from 2023. In 2024, pharmaceutical and medicinal products accounted for 30 per cent of Northern Ireland exports to US, and specialised machinery for industries such as agriculture and mining came to 17 per cent of exports.

After the signing of the UK-US trade deal on May 8 2025, all exported goods from Northern Ireland entering the US market are subject to 10 per cent tariffs. The EU-US struck a trade deal on 27 July 2025, introducing a tariff ‘ceiling’ of 15 per cent on EU imports to the US. This created a tariff border on the island of Ireland, arguably giving the North a competitive advantage over the Republic.

Under the terms of the EU-US deal, most EU products will be subject to a tariff rate higher than a 15 per cent ‘ceiling’ when entering the US market, rendering the Most Favoured Nation Rate currently imposed on all US-bound imports as per World Trade Organization rules obsolete for EU imports to the US. Tariffs on UK goods are ‘stacked’ on top of these rates – which vary depending on the good in question, meaning some UK goods, such as clothing, will face higher tariffs than their EU equivalent.

Net benefit or net detriment?

The effects on Northern Ireland appear to be mixed, with Minister for the Economy Caoimhe Archibald MLA dismissing the idea of a competitive advantage for the region by saying: “This [tariff border] is in no one’s interest.” A report issued by the Department of the Economy titled, The Direct Economic Impact of the New USA Tariff Regime on the Local Economy, predicts a sustained 0.15 per cent contraction in Northern Ireland GDP owing to tariffs.

According to Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize winning Economist, EU firms could “trans-ship [their] goods through Northern Ireland to get the lower tariff rate”. This could lead to economic benefits such as increased cargo volumes at Northern Ireland ports, stimulating economic growth.

Analysis

According to US President Donald Trump, ‘tariff’ is the “most beautiful word in the dictionary”. While his position on everything from abortion to party allegiance has been fluid, his protectionism is a rare continuous theme, speaking to The New York Times in 1988, he said: “I believe very strongly in tariffs… America is being ripped off. We are a debtor nation, and we have to tax, we have to tariff, we have to protect this [US] country.”

On 2 April 2025, dubbed ‘liberation day’ by the White House, the global economic order was thrown into disarray. Trump declared a national emergency regarding the US’ national trade deficit and announced “reciprocal tariffs” on friend and foe alike.

On cue, world leaders issued a single diktat to their diplomats in Washington DC – secure a trade deal. The UK was first, solidifying the 10 per cent baseline tariff with limited carve outs for steel, aluminium, cars, and aerospace parts. The EU followed, with a 15 per cent tariff ‘ceiling’. With 10 per cent being lower than 15 per cent, the UK appeared to ‘win’ the trade war.

However, the lack of an anti-stacking provision in the UK-US trade deal leaves some UK goods facing higher tariffs than their EU equivalents, meaning Northern Ireland’s so-called ‘competitive advantage’ may only exist on paper.