Unemployment low but economic inactivity remains high

Northern Ireland’s high rate of economic inactivity, when compared to the rest of the UK, is being masked by one of lowest ever rates of unemployment, writes David Whelan.

The latest Labour Market Report compiled by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) for March to May 2018 shows an annual decrease in the unemployment rate to 3.5 per cent and an increase in the employment rate to 69.8 per cent.

Further statistics from the Labour Market Report show a decrease in the claimant count by 1,800 in the year to June 2018 to 28,600 and an annual increase in redundancies of 23 per cent, with 2,848 over the 12 months. The total employee jobs total at March 2018 was 763,440, an increase of 2.5 per cent over the year.

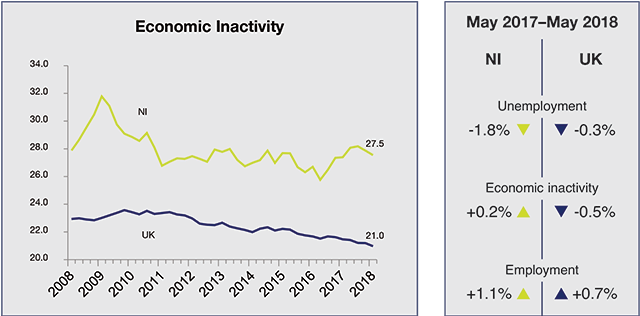

While Northern Ireland’s move towards full employment (a 3 per cent unemployment rate is typically described in this way) is to be welcomed, the figure somewhat masks Northern Ireland’s high economic activity rate of 27.5 per cent.

To offer context, the Northern Ireland economic inactivity rate continues to be the highest of all the UK regions and well above the UK average figure of 21 per cent. While the UK is now displaying its joint lowest level of economic inactivity on record, Northern Ireland’s rate has changed little over the past five years.

To some extent, this can be explained by further comparison. The headline figures show that Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate is below the UK rate (4.2 per cent), the European Union rate (7.1 per cent) and the Republic of Ireland rate (5.9 per cent).

However, when comparing actual employment rates, Northern Ireland is 69.8 per cent compared to the significantly higher UK rate of 75.7 per cent.

Although Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate is low, almost 60 per cent of those unemployed are classed as long-term unemployed, meaning they have been unemployed for 12 months or more.

Overall, the headline figures somewhat distorts the reality of the labour market and wider economy in Northern Ireland. While the unemployment rate is falling, many of the employment prospects that exist are low-skilled and low-paid. Coupled with a large cohort of working age people who are not working and not seeking or available to work, there exists a productivity problem.

Gross Value Added (GVA) per head in Northern Ireland has never reached the UK average and is currently falling further behind it, according to NERI senior economist Paul Mac Flynn. He highlights that in 2016 total output per person in Northern Ireland was 77.6 per cent of the UK average. This is even lower than the 81.5 per cent recorded in 2006.

As well as this, Northern Ireland is consistently ranked as one of the lowest paid regions of the UK and has never reached the UK average median weekly wage since data collection began. The median weekly wage in Northern Ireland was 92 per cent of the UK average in 2016.

According to the OECD, Northern Ireland has the lowest rate of skills mismatch of any OECD economy, with only 9 per cent of workers feeling they do not have the level of skills required to do their job. Considering that in 2016, 16 per cent of 16 to 64-year-olds in Northern Ireland did not have a level 1 National Vocational Qualification (NVQ), meaning less than 5 GCSEs at A-C grade, a reasonable conclusion is that a large proportion of employment in Northern Ireland is relatively low quality when compared to other UK regions.

Mac Flynn supports this assumption through analysis of the context in Northern Ireland where workers do not feel incentivised to upskill because of a lack of skilled job opportunities and firms engaged in low value-added production because they do not feel there is a sufficient skills base to grow from, adding: “Northern Ireland is in essence trapped in a low productivity, low wage and low skilled economic dynamic”.

He explains that a problem for Northern Ireland is that it appears stuck in a supply and demand cycle, whereby the supply of skills in the labour market is directly linked to what people perceive the demand for skills to be: “It would appear that workers are not incentivised toward upskilling and firms have little appetite for investment; and because these two positions are well matched, nothing is likely to change.”