Productivity on the island of Ireland: A tale of three economies

The border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland has come to dominate the negotiations surrounding the UK’s exit from the European Union. The future of this border is important for many political, social and cultural reasons, but the main sticking point in these negotiations appears to be economic, writes Nevin Economic Research Institute senior economist, Paul Mac Flynn.

The shape of the UK’s future trading relationship will be determined in large part by the necessity of an open trade border on the island of Ireland. Preserving the current economic integration between the two economies has taken on a level of importance that has not been seen in recent years. The all-island economy was a concept which was very much in vogue in the years following the Belfast Agreement, but it never quite lived up to expectations and slowly fell away from the policy discourse. Brexit has brought the issue to the surface again and it provides an opportunity to examine the state of both these economies and whether we are any closer to the all-island economy goal.

With this in mind, my colleagues and I at the Nevin Economic Research Institute have recently published a piece examining productivity on the island of Ireland. Productivity is a good, if imperfect, measure of economic performance. It measures how efficiently an economy uses the resources available to it to produce output (Gross Value Added). This performance ultimately determines the wealth created in an economy and should determine living standards for those within it.

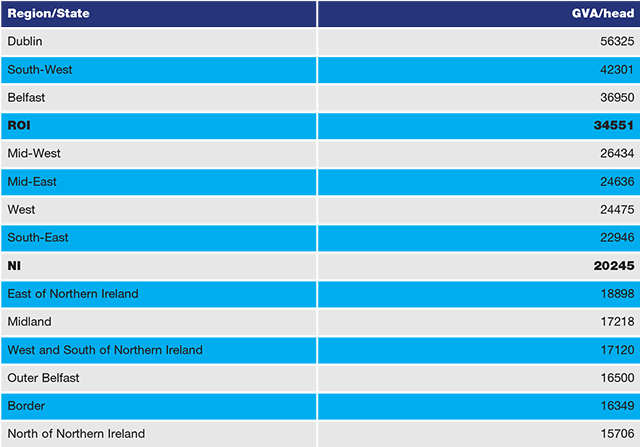

The first thing to be said is that there is quite a regional variation in productivity performance on the island of Ireland. The most notable result is that Dublin is so far out in front, with a level of value added per person almost double that of the all-island average. Northern Ireland fares badly with only Belfast making the top half of the 13 sub regions on the island in terms of value added per person. (see figure 1)

A large part of this story is the explosion in foreign direct investment (FDI) into the Republic of Ireland – primarily the opening of subsidiaries by large multinationals. This influx has had real effects on the southern economy but it has also flattered measures of output. This has become startlingly clear in the era of “leprechaun economics”.

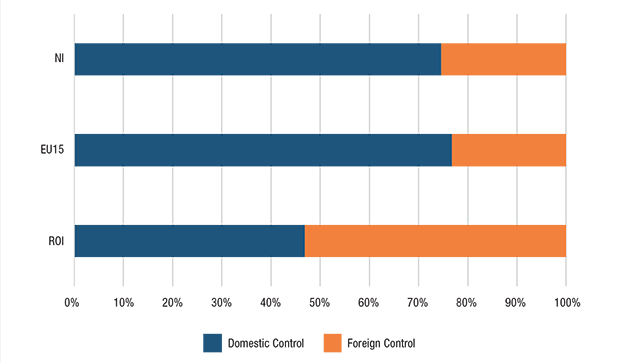

The impact of FDI has been such that it is now more accurate to speak about three economies on the island of Ireland rather than two. One is an apparently world beating foreign controlled sector based around Dublin and Cork for the most part, another is a modestly performing domestic economy in Ireland and finally we have an underdeveloped economy in Northern Ireland (see figure 2).

The foreign controlled sector contributed over half of the Republic of Ireland’s output in the business economy in 2014; double that of Northern Ireland and similar EU countries demonstrating the scale of that economy in the Republic of Ireland. That sector looks exceptionally productive compared to EU averages for foreign controlled firms, registering output per worker over double the average levels. This is particularly concentrated in ICT and Manufacturing, sectoral homes to some of the tech and pharma giants that have had such a large effect on the statistics (see figure 3).

The presence of this sector has, however, masked a more mixed picture in the domestic economy of the Republic of Ireland, where most people in the country work. While the last few years have seen an improvement in productivity here, this economy has some concerning weaknesses. It is disproportionately concentrated in low productivity and low wage activities, such as hospitality and retail. Its manufacturing sector is only around half the size of domestic manufacturing elsewhere in Europe. Most surprisingly, domestic IT firms have underperformed compared to EU averages.

Northern Ireland, however, has fared worse. It too has received foreign investment, and while this has not been on the scale of the Republic of Ireland, it is above EU averages. Despite this, Northern Ireland consistently underperforms and lags behind in nearly every sector. Northern Ireland only manages to come second in one sector, Wholesales and Retail, but only just.

These statistics point to a challenge for policy makers north and south. For too long, governments have assumed that the mere presence of world leading multinationals would lead to the economy as a whole gaining a productive edge. Our statistics complicate that story and suggest that that this has not happened for the domestic economy in the Republic of Ireland. The statistics also suggest that, if anything, the effect in Northern Ireland has been even weaker. Northern Ireland hasn’t even managed to measure up against the domestic side of the Republic of Ireland’s economy, never mind the foreign sector.

The value in FDI goes beyond the immediate output numbers or the employment they directly generate, important as that is. If the benefit of FDI does not spill over into the rest of the economy, then we are merely ‘buying in’ success. The true benefits extend to the indirect potential boost it can give the whole economy in terms of technology, innovation and expertise.

The Republic of Ireland economy at present appears to be a world leader with economic growth next year projected to be the second fastest in Europe. However, FDI isn’t always forever. Take away a few foreign firms and the Republic of Ireland’s economy begins to look very ordinary. This should worry policymakers, especially in the current global economic climate.

For Northern Ireland, this research should concentrate minds on the state of domestic industry. How is it that above average levels of FDI have not impacted at all on productivity? What is it that prevents domestic firms from integrating with and benefiting from FDI? These questions need to be answered before any new industrial strategy can begin.

For both economies, skills appear to be a key issue. Infrastructure, and broadband in particular, also appear to be an obstacle to growth spreading beyond city regions and into the broader economy. The focus needs to be on investing in the skills and talents of the people of this island to ensure that we reap the benefits of an increasingly globalised economy. In the face of Brexit and an uncertain future, that task should start now.