Place-making in the public realm: Eilis O’Connell

Central to the North West is its world-renowned scenery, and the community of artists who have drawn inspiration from it. Niall Coleman speaks to the award-winning Derry-born sculptor, Eilis O’Connell, about place, the past and creating art in the public realm.

Tell us about your inspiration and first experiences as an artist.

The need to make things is in my DNA. The obsession continues.

I recall my father building a boat — he had been in the Irish Navy and had a great love of the sea. I watched him turn sheets of plywood into amazing forms, leaving discarded wood for me to play and build shelters with. I still remember their shapes and colours. So, even as a child, I was making little secure spaces for myself, in a very sculptural way. This was important, being the eldest of six children.

My mother was good with her hands – she knitted, made clothes for us and encouraged us to be creative. Three of my father’s brothers painted landscapes, so our house was awash with oil paintings of different parts of Ireland. When my parents died, the only things in the house we really cared about were those paintings that we grew up with. We lived near an Grianan of Aileach, and summertime visits there formed my first experiences of what sculpture could be.

Much of your inspiration and development has inevitably come from your study in Boston during the 1970’s. How has being a Derry-born woman abroad influenced the perception of you by others?

It was so great to get away from Ireland; you got a chance to re-invent yourself. As an artist, I choose not to deal with politics or women’s issues in my work — but of course, these things did affect my daily life. I tried to take a balanced view, but I felt it most when I lived in London in the late 80s and 90s, when there were IRA bombing campaigns, and no-one felt safe in the city. There was never any hostility about being Irish; London was my home for 17 years.

I got two large commissions on sites that were bombed by the IRA in London: 99 Bishopsgate and Marsh Wall. Bishopsgate was commissioned after the bombing, and John Major opened the rebuild. I was to attend the opening, although because my CV mentioned that my birthplace was Derry, I couldn’t get security clearance. I thought it funny, although my agent was raging. Later, I got a prize for that work from the Royal Society of Arts. Marsh Wall was more serious. The contract wasn’t signed, and a bomb killed two men at the newspaper stand opposite the site. I had been there with landscapers the day before. That really unnerves you, and I thought that being Irish, this commission would never happen. Two years later, we built it.

Do you feel that ‘public art’ is a more developed concept in other parts of Europe? Tell us about your experiences with The Great Wall of Kinsale.

In 1986, I was commissioned by the Arts Council of Ireland to make a sculpture in Kinsale. I did three public presentations in the town, explaining my perfectly made scale model and the nature of COR-TEN steel. Towards the end of that process, a local councillor said that no one liked my sculpture, and asked if I could make something like a fisherman instead. I knew that I was in trouble, but there was no way I could turn back. The row got very nasty and personal, with locals demonstrating at the opening. The county architect declared it a danger to the public and changed it without my permission. I tried to take out an injunction to stop this. However, I discovered that I didn’t own the copyright, as Ireland hadn’t yet ratified the Berne Convention. My only option then was to disown it. Now, artists are protected from this kind of interference.

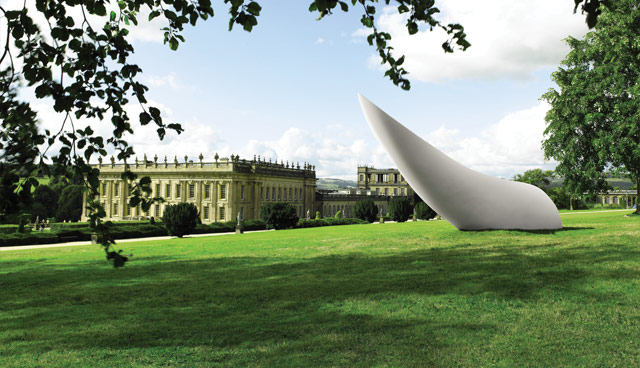

When art is placed in public, it becomes part of the environment. So, the context into which it is placed must be sympathetic and appropriate. It is place-making in the public realm. Sculpture can give place a unique identity. The modern environment has become bland, and we need artistic intervention to make places memorable.

How do you feel about the influence of computer-assisted design (CAD) technology upon the arts?

When I started working in metal, I did everything myself, including cutting, welding and grinding. I was very independent in what was a very male-dominated profession. I persevered, and went to welding classes in the tech. I loved welding — to me, it was like sewing. I now use laser-cutting firms to cut shapes in metal, and foundries and fabricators for big works. My studio is where I experiment and develop ideas. I work with metal, bronze, steel, resins and composite materials. Currently, I am in the process of setting up a sculpture garden on the hilly acre around the studio. It’s hard for people to visualize what a small sculpture looks like when scaled up. The Irish landscape is so beautiful, so I’m finally doing it.

Everything is digitized, and I think it’s sad that many contemporary artists do not get the opportunity to physically work with their material. Designing in virtual reality, there is no weight, gravity or haptic quality to the materials used. So, the actual problems that arise are passed on to others, and in that way, artists lose control.

Do you feel that a changing Ireland is allowing for greater space for women in the arts? How can female participation in Irish arts be greater facilitated?

Now is a great time to be a woman in Ireland. We have changed very quickly from a narrow-minded, Catholic enclave to a liberal and just society. I’m very proud of that progress. Communities had to tolerate the dictatorship of the dysfunctional.

In Ireland, I want to know why male artists get higher figures for their work. It is a worldwide problem, but it also exists here. Whatever their gender, an Irish artist must be strong to survive, because the market is small. I think the commercial galleries could be a lot more ambitious. We need to be shown abroad, and that means International Art Fairs, which are hard work and very costly. More women running commercial galleries might be the answer.

Considering your own experiences of the Irish border, how do you feel about the impact of Brexit upon relationships in society?

I lived on the border of Donegal: that imaginary line that divides a landscape. It always intrigued me, because it’s not physically there. A hard border would breed mistrust. It would wreck the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Technical solutions don’t work with human beings, because there is a way around everything. Brexit is such a massive waste of energy. It is a concept that offers no understanding of the reality of dismantling 40 years of workable legal and trade agreements. This is more about personal political ambition; the concept of ‘the greater good’ does not come into it. I’m hoping that some legal loophole will emerge and trigger a second referendum — but then, I’m an optimist.

Growing up in Donegal was important — that environment made me who I am today. The unspoilt nature, spectacular landscape and a stunning coastline will always attract people.

If you add to that broadband and easier access by road, it becomes a place where people can thrive and progress with the business of living.