Education, equality and the economy

Political partisanship has prevented positive changes to Northern Ireland’s education system, a report by leading academic Tony Gallagher has stated.

Assessing through the lens of education whether the shared political arrangements since the Good Friday Agreement have lived up to their promise of providing a means for encouraging good governance in a divided society, Gallagher, a professor at the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast, finds that “our fractious political system” has made it difficult to generate consensus on key educational issues and promote a discourse of the “common good”.

This goal, he states, is not helped by a school system mainly characterised by division, where responsibility for different aspects of education in government seems to operate in silos and “focuses too often” on a narrow set of quantitative indicators that serve as short-term outputs, rather than long-term outcomes.

In advocating for a roadmap to an education system that combines excellence with equality, Gallagher requests a recognition of “the shockingly high levels of inequality in educational outcomes caused by social background” and suggests a “grander vision” of the aspirations for young people’s educational achievements, one that is not only focussed on GCSE grades.

The Education, Equality and the Economy study recognises that schools, and Northern Ireland’s wider education system, face challenges similar to those found in most western countries, but have the added responsibility of preparing young people to live and work in a society characterised by division and violent conflict, while equipping them to contribute towards a shared and better society.

“A society that cannot deal with the legacies of a difficult past, or help its citizens engage successfully with difference, is not one which will encourage a settled, democratic society and develop a sustainable, thriving economy in which all its citizens will benefit,” Gallagher states, outlining that the purposes of education are interdependent.

The defining differences of Northern Ireland’s education system when compared to most OECD countries is the relatively young age at which compulsory education starts; the continuation of a selective system of post-primary education; and the significant role of the churches in education governance.

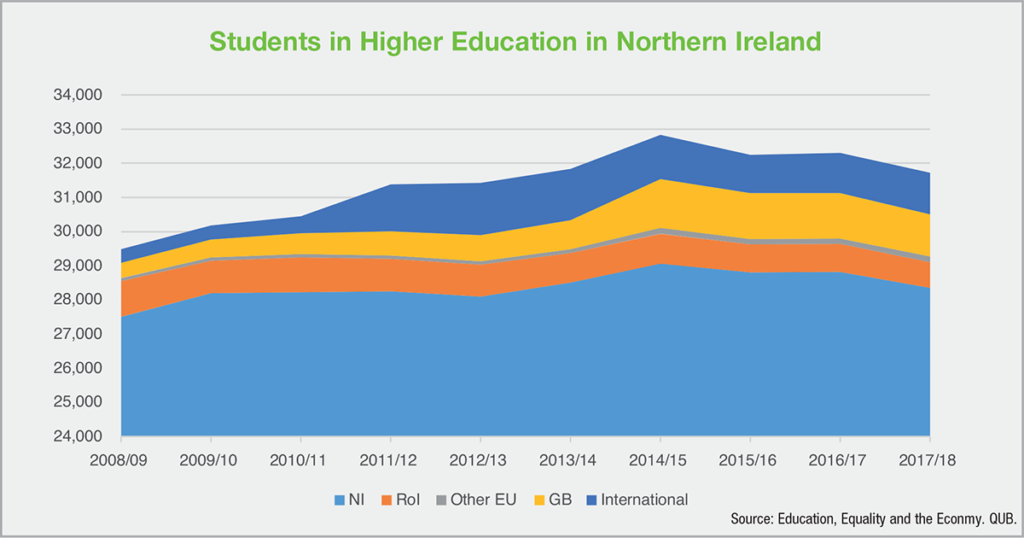

Since the Good Friday Agreement, the patterns of change among schools and students include an initial significant decline in student numbers, particularly in primary and rolling into secondary schools, which is now growing again. The fallout of the enrolment decrease was recognised mostly by secondary schools, with grammar schools maintaining or increasing their numbers through an increase in the proportion of students they admitted.

The number of students entering special schools have grown more recently. There are 5,700 students in special schools but 25 per cent of students are deemed to have special education needs in the system as a whole.

Irish Medium Education (IME) schools and student numbers have recognised a marked growth, coupled with a “steady” rate of growth in integrated education schools. However, the rate of integrated education pupils has stabilised recently after a period of growth. Additionally, the number of ‘newcomer pupils’ has grown in almost all forms of education, apart from grammar schools.

Achievements

Despite the ending of the publication of official school performance tables, publication of league tables through freedom of information gathering means they remain an indicator for parents of educational value and pressure remains on schools to maximise their performance levels.

Gallagher, through his research, outlines a number of influences on the reliability of the data available to assess achievement patterns, not least, that only aggregate data is available, most of which is at the level of individual schools.

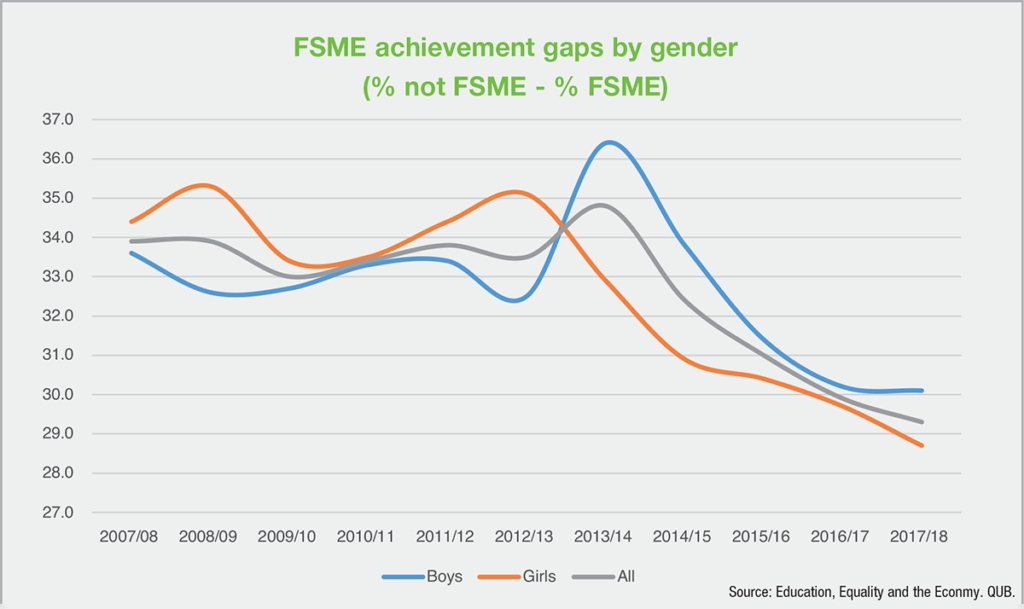

Measures of performance have mostly relied on the percentage of school leavers achieving five or more GCSEs grades A*-C, 85 per cent in 2017/18. Girls tend to fare better than boys in this regard, although the gap is narrowing. There is no evident gap between the achievements of Protestant and Catholic pupils.

When the performance measure is five or more GCSEs grades A*-C including English and Maths, which the Department of Education has tended to focus on since 2008/09, the percentage of pupils achieving this outcome has risen from 59 per cent in 2008/09 to 71 per cent in 2017/18. A small gender gap is favourable to girls. No achievement gap is instantly recognisable between Protestant and Catholic pupils but, factoring in the number of leavers in each group, the rise for Protestant pupils in this measurement is 200 compared to 1,000 for Catholic pupils.

The percentage of school leavers achieving three or more GCE A Levels grades A*-E has increased from 49 per cent in 2008/09 to 53 per cent in 2017/18. Since 2008, the number of Protestant boys meeting this criterion has declined by 180, while the number of Catholics had increased by 300.

The study recognises the influence of social disadvantage as a variable in performance. Highlighting the “strikingly wide” achievement gaps gender and social background influence, it highlights that the proportion of Catholic girl leavers from affluent households with five or more GCSEs (grades A*-C, with English and Maths) is 46 percentage points higher than the proportion of Protestant boy leavers from social disadvantaged households.

“It is worth noting the level of attention that is focused on gender, and perhaps even more so religious achievement gaps, but while significant, these achievement gaps are much smaller than the achievement gap linked to social background,” says Gallagher.

It often appears that responsibility for different aspects of education in government seems to operate in silos, within and between departments, and focuses too often on a narrow set of quantitative indicators that serve as short-term outputs, rather than long-term outcomes.

— Tony Gallagher

“Indeed, it is difficult to understand why this is not perceived more generally as a scandalous circumstance and subject to urgent and immediate interventions.”

On leaving school, a pattern for Northern Ireland suggests that girls are more likely to go to higher education than boys and Catholics are more likely to go than Protestants. Protestants are more likely to go to further education than Catholics, with boys a little more likely than girls.

Pupils entitled to free school meals are much less likely to go to higher education, in comparison with pupils not entitled to free school meals, and this effect is greater for boys than girls.

Funding

Gallagher outlines that Northern Ireland’s universities are in a “disadvantaged position” in relation to the level of funding they receive for teaching purposes in comparison to other regimes across the UK, a long-standing argument in relation to Northern Ireland’s education system. However, as he points out, more recently attention has been diverted to the funding crisis facing schools.

Gallagher believes that the basis for the current funding crisis in schools derives from the way in which the Age Weighted Pupil Unit (AWPU), which provides the basis for the level of per-pupil funding each school receives, is calculated. Despite cash increases, in real terms the budget decreased by over 10 per cent between 2013-2017, despite a rising pupil population.

“In recent years in Northern Ireland NIAO (2018) highlighted a ‘double-hit’ on schools, with an education budget that is falling in value, and increasing pupil numbers, so that the value of the AWPU has fallen considerably. The greatest impact of this has been on primary schools as this is the area where pupil numbers are rising,” Gallagher states.

Identifying some particular case studies in relation to how politics has shaped the evolution of the education system since the Good Friday Agreement, Gallagher describes the academic selection debate as representing “the inability of shared government to find the compromises that might have allowed them to pursue a solution”, and adds that the “abject failure” by parties to work cooperatively towards an agreed outcome and the common good.

On the push to rationalise the public service, with a key focus on education, Gallagher believes that as was the case with academic selection, “the review of public administration also seems to represent a significant failure of shared government”. Discussing the multiple delays and barriers to the Review of Public Administration in Northern Ireland’s (RPANI) ambition to establish a new single Education and Skills Authority, which was included in the 2001 Programme for Government, and abandoned in 2014 in favour of the establishment of the Education Authority, Gallagher summarises: “The original goal of a single strategic authority may have been overly-ambitious, given the institutionalised diversity of the education system in Northern Ireland, but in the end the review process lasted much longer, and costed much more, than had ever been envisaged; it resulted in the consolidation of the five Education and Library Boards into a single authority, but one without the strategic authority or responsibility that had been intended; and ended up with more NDPBs than had existed at the start, when the original intention had been to incorporate them in the single authority.

“There is also little evidence to suggest the process saved significant funds for investment directly into schools,” he adds.

Economy

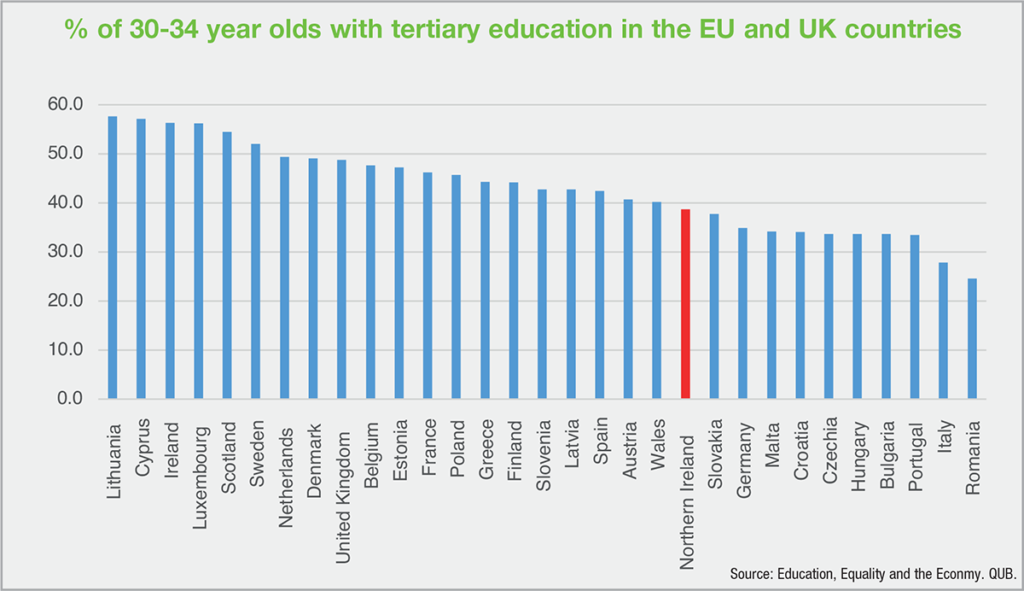

The academic highlights the important roles of education to enhance the human capital of society by strengthening the skills base, an area where Northern Ireland has struggled in comparison to other EU countries.

Pointing to patterns which highlight Northern Ireland’s comparative skill base weaknesses and the challenges that presents, Gallagher adds: “In addition, Northern Ireland is disadvantaged by the fact… that it exports a high proportion of young people who enter university in England or Wales, only a small proportion of whom ever come back to settle in Northern Ireland.”

Gallagher suggests that his analysis is evidence that the educational challenges identified are not just matters of concern for education but will affect the economic capacity and potential of Northern Ireland.

Shared society

Despite the widespread recognition of the potential of the education system to contribute to reconciliation, even before the Good Friday Agreement, Gallagher assesses that a series of interventions, including the development of new curriculums and deployment of contact programmes between communities at school age and the development of Integrated Education, had “limited” impact “in part because the education system as a whole never placed this role as a key and meaningful priority”.

The academic outlines his belief that there remain challenges in the fulfilment of the social goal of reconciliation, stating: “We have one of the most impressive citizenship curriculums in the world, but within the wider school curriculum it is probably accorded the lowest status.

“It is hard to escape the conclusion that education could do a lot more to empower young people to believe that a better, shared world is not only possible, but achievable. But it is hard for schools to promote this sense of efficacy when we can see so many examples of education policy where political partisanship has got in the way of the common good and a positive response to challenges that have such negative consequences for the whole of society,” explains Gallagher.

He summarised that his evidence suggests that a “fractious political system” has made it difficult to generate consensus on key educational issues and promote discourse of the common good.

“That we also have a school system that is mainly characterized by division probably does not help in that goal. It often appears that responsibility for different aspects of education in government seems to operate in silos, within and between departments, and focuses too often on a narrow set of quantitative indicators that serve as short-term outputs, rather than long-term outcomes,” he adds.

Gallagher recommends changes to the education system and asks the question: “What if we were to commit to a goal that, by the time every young person completed their time in education, they would have the qualifications, attributes and attitudes that would allow them to live fulfilled lives as citizens?

“This would involve a recognition that we would not necessarily provide all with the same outcomes, but that all outcomes would be valued,” he states. “To refocus our goals for education in this direction would also require a recognition that the shockingly high levels of inequality in educational outcomes caused by social background is an immediate and pressing priority that has to be tackled as a matter of urgency, and that this challenge can only be addressed by a joined-up approach across all areas of government and the involvement of wider societal stakeholders”

He concludes: “It is clear… that we need to deepen and broaden our understanding of the process affecting education patterns and outcomes, and that for this we need better data in order to understand the routes young people take through education and provide better advice on opportunities and outcomes.

“Most of all we need to escape the silos in education, not only within levels, but across them. Schools, further education colleges and higher education institutions all form an interdependent network of routes, yet we do not provide a roadmap of opportunities that show how people can access, assess and navigate those routes to best benefit.

“If we could provide such a roadmap it might also help us identify the pinch-points where arbitrary barriers to progress exist. And if we could achieve all this then perhaps, we might be able to aspire, realistically, to an education system that combines excellence with equality. This has been achieved elsewhere and there is no good reason why we should not achieve this in Northern Ireland.”