‘A project too far’

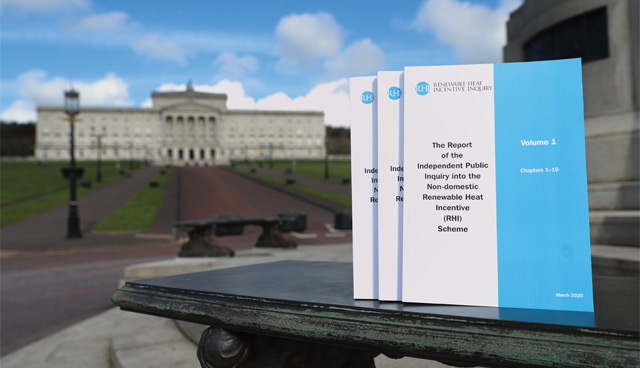

Far from the politically damning findings expected from the RHI public inquiry, the limited reproach of Sir Patrick Coghlin’s delayed report will come as a relief to many of those involved in the Northern Ireland Executive’s biggest and most expensive scandal.

Although not the headline finding, the most striking line in the more than 650-page report and recommendations, following the conclusion of the £14 million public inquiry, is that “there is no guarantee that the weaknesses shown in governance, staffing and leadership… could not combine again to undermine some future initiatives”.

Coghlin and his team have effectively said that such are the failings in the mechanisms of governance in Northern Ireland that even with the lengthy list of reforms outlined, the relevant safeguards still don’t exist to prevent the extreme mishandling of public funds.

Change has been recommended, however. The Northern Ireland Civil Service bore the brunt of most of the report’s criticisms and a subsequent inquiry into any potential misconduct of officials has been announced by Finance Minister Conor Murphy. Also, codes of conduct have been recommended for both special advisors and ministers. However, these are restrained changes in comparison to what might have been expected.

“Corrupt or malicious activity on the part of officials, ministers or special advisers was not the cause of what went wrong with the NI RHI scheme,” Coghlin found. For those who watched the evidence given to the public inquiry or read journalist Sam McBride’s ‘Burned’, such a finding appears lenient in respect of the successive errors, misleading information and sharing of information to third parties, including family members and big business, that occurred.

McBride’s direct, cogent and swift analysis of the flawed RHI scheme and the internal workings of government in its delivery and eventual closure, is in stark contrast to the well over 250,000 word report delivered on 13 March by Coghlin.

Of course, much of McBride’s book is based on the publicly accessible evidence given to the inquiry. He himself makes the point that the transparent nature of the inquiry has potentially reduced the shock factor that may have been associated with the final report had most of the evidence not already been in the public domain.

However, while some of the findings are sobering, especially those made on the poor levels of oversight, expertise and collaboration, of the former Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI), there is little evidence of the shock and frustration witnessed of Coghlin and his team while hearing the 111 days of evidence. To this end, many of the recommendations appear blatantly obvious in light of what has been revealed.

Rigorous scrutiny in determining the skills and resources for new policy; training for, and to better inform, ministers; an induction process for SPADs; better handling of the timing of staff moves; and compliance in note taking, to name a few, are not radical measures.

Politicians involved in the failure, while not immune from criticism, were largely absolved of blame. Arlene Foster, the minister who set up the RHI scheme and the Finance Minister at the time it ran out of control, was “repeatedly given inaccurate or misleading information” about RHI by some of her civil servants, the report states. In the lead up to the inquiry’s report it had been suggested that findings against Foster might be so damning that it could undermine her current position as leader of the DUP and Northern Ireland’s First Minister. That is far from the case and Foster’s decision not to step aside for a previously suggested ‘in-house’ inquiry now appears vindicated.

Foster, who signed an incorrect draft Regulatory Impact Assessment, should not have done so, the report says. She admitted in the inquiry’s evidence that she, as Minister, had not fully read the RHI regulations, which were later presented to the Assembly for their approval. Unsurprisingly, the report says that the division of responsibility between Foster and her long-term SPAD Andrew Crawford for reading, analysing and digesting important documents “was ineffective” and led to “false reassurance on the part of the Minister, and potentially of officials, as to the level of scrutiny applied to detailed technical reports provided to the Minister”.

Corrupt or malicious activity on the part of officials, ministers or special advisers was not the cause of what went wrong with the NI RHI scheme.

Foster has apologised and vowed to learn from her mistakes, however, the TUV’s Jim Allister asserted: “In any other jurisdiction it is hard to imagine that heads would not roll.

“But here, even the concept that the buck stops with minister when a department spectacularly fails, has become so muted that a pre-emptive apology seems to do,” he adds.

Similarly light, was criticism of Foster’s political colleagues. The flawed legislation passed swiftly through the Enterprise, Trade and Investment Committee, the cross-party Assembly committee responsible for scrutinising the Department. The inquiry found that the committee did not operate as an effective check against departmental error in the case of the RHI scheme but elaborated: “the ETI Committee was not provided with sufficient/adequate information to permit the ETI Committee to effectively discharge its scrutiny function”. The flawed scheme also passed through the 108-member Assembly unchallenged.

Foster’s SPAD, Andrew Crawford and the actions of other SPADs appear to have been collectively earmarked for resolution through a proposed new code of conduct (something the Executive has already pre-empted and rolled out without the full findings). Despite lengthy evidence during the inquiry around use of personal emails, unnecessary delay in implementing cost controls and the passing on of various confidential documents to third parties, the language of the report is restrained, simply referencing “unacceptable behaviour”.

As outlined, the major reforms and criticisms are of the Civil Service. “Inaccurate, incomplete or misleading” documents or advice to ministers, failure to review and the “absence of relevant and appropriately tailored project management processes”, were just some of the scathing criticism levelled at those working alongside the political decision-makers.

“The sad reality is that, in addition to a significant number of individual shortcomings, the very governance, management and communication systems, which in these circumstances should have provided early warning of impending problems and fail-safes against such problems, proved inadequate,” Coghlin’s report said.

Coghlin has wisely installed a measure to ensure his lengthy report does not gather dust and follow a similar fate to other inquiries that have recommended change to how governance is administered in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland’s Comptroller and Auditor General has been asked to monitor and, if necessary, peruse effective implementation of the recommendations. This will at least ensure that the handling of the scheme, which undermined public confidence in the Stormont administration, will not completely evaporate from the public conscience.

That being said, scepticism exists as to whether the report was forceful enough to inspire the radical changes needed to ensure that the failures of a scheme, with an original projected overspend of £500 million and which has left Northern Ireland as the only area in the UK or Ireland without a government subsidy to promote renewable heat, could not happen again. Afterall, Coghlin himself has raised doubts.