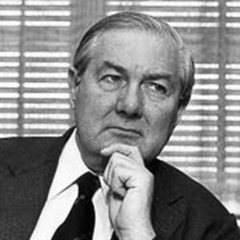

The Terence O’Neill legacy: 50 years on

Peter Cheney reviews the premiership of Terence O’Neill, a moderate leader overshadowed by the hostility of the early Troubles.

Peter Cheney reviews the premiership of Terence O’Neill, a moderate leader overshadowed by the hostility of the early Troubles.

“What kind of Ulster do you want?” was the compelling question asked in Prime Minister Terence O’Neill’s crossroads speech as 1968 drew to a close.

The choice, he said, was between a “happy and respected” province in “good standing” with the rest of the UK or “a place continually torn apart by riots and demonstrations and regarded … as a political outcast.”

O’Neill pointed out to unionists that support from Britain could not be taken for granted. He also appealed to civil rights campaigners to come off the streets and allow “an atmosphere favourable to change” to develop.

His aim was that “in every aspect of our life, justice must not only be done but be seen to be done to all sections of the community.” Yet, within a few short months, O’Neill was out of office and the province was approaching the “brink of chaos” which he had predicted.

Terence O’Neill was born in London in September 1914. His family was aristocratic and Anglo-Irish. His father died in the Battle of the Marne shortly after his birth.

Publicly schooled, he travelled extensively in his younger years and served as an Irish Guards captain. A moderate by upbringing, O’Neill always remembered the kindness of a Dutch Catholic family who cared for him when he was injured at the Battle of Arnhem. He was also very aware of the cost of conflict by that time: his older brother, Brian, and his best man, David Peel, both died in battle.

He moved with his family to Ahoghill and was elected (unopposed) for Bannside in 1946. He was briefly Minister for Home Affairs in 1956 and then promoted to Minister of Finance later that year.

O’Neill was chosen to succeed Basil Brooke as Prime Minister in March 1963 and deliberately styled himself as an economic moderniser.

The M1, the University of Ulster, the drive for inward investment and modernist architecture in Belfast were all signs of progress although nationalists protested that the west was neglected and discrimination continued. Nationalist hopes were raised by O’Neill’s unprecedented meetings with Taoisigh Seán Lemass and Jack Lynch and visits to Catholic schools.

As the civil rights movement grew in momentum, divisions within the UUP sharpened. O’Neill and his supporters struggled to win support for ‘one man one vote’ in local government elections. He resigned as Prime Minister in April 1969.

“In many ways, he was much more presentable outside Northern Ireland than in it,” Ken Bloomfield recalls.

O’Neill had “relatively little contact” with the province until after the war.

Bloomfield was his private secretary in the finance ministry and speech-writer as Prime Minister.

“It’s fascinating that, even though he was the least bigoted of men, almost automatically he joins the Orange Order,” Bloomfield recalls. He was the only person who ever took Bloomfield to an Orange event: the County Antrim Twelfth at Ahoghill.

The Orange membership was probably for electoral reasons. O’Neill, he suspects, would have preferred a Westminster seat but ran for Bannside as this was unavailable.

“Very much, in those days, the ex-Irish Guardsman,” he says of his first impressions. “The toothbrush moustache and he’d very much an Etonian accent. It’s funny, you know, people rely very much on impressions and he couldn’t help sounding to the average Ulsterman as rather posh and rather snobbish.”

In Bloomfield’s view, this was “a misreading” of the man with whom he worked daily: “He was actually the least snobbish of men but he spoke the way he spoke and I’ve often said, only half seriously, that if he’d been to Ballymena Academy rather than Eton, he might have had a very, very successful political career.” The accent was combined with a certain shyness: “At some gathering, he would throw his head up like a startled horse and you just knew that he wanted to get away.”

Bloomfield contends: “I think one of the great mistakes in looking at politicians is to assume they’re all extroverts. I think quite a lot of them almost do it against the grain of their own personality.”

O’Neill “wasn’t very clubbable” and indeed was “clearly more comfortable” with his close officials. Bloomfield and the PM’s other confidants – Harold Black and Jim Malley – were known “not very affectionately as the presidential aides.” O’Neill regularly had lunch with them but they sometimes told him: “Look, Prime Minister, we’re working for you but your position’s actually dependent on these other people.”

He sees some parallels with Ted Heath. A politician with an “unfriendly personality” can “get away with it when all is going well politically” but when crises come “that’s when you need real friends in politics, who like you and admire you and will stick with you through thick and thin.”

Wider links

O’Neill was in his element when visiting Lyndon Johnson at the White House – another first for a Northern Irish leader – or promoting Northern Ireland at Westminster or in Europe.

In June 1966, Bloomfield travelled with O’Neill to France to mark the 50th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme. At the British embassy in Paris, the call came through about the shootings in Malvern Street by the newly formed UVF. A Catholic teenager, Peter Ward, was killed in the attack.

“Mrs O’Neill stays behind. Terence and I rush back, get back at midnight and proscribe the UVF. But then back again to the great commemorations on the battlefield.”

O’Neill did not set out with a “grand plan” to reform Northern Ireland but this “grew organically”. He was cautious and often preferred “gesture politics … saying the right thing and not always very good at doing the right thing.”

For much of his time in office, he chaired the Cabinet rather than leading it. He started to take the lead when Westminster added more pressure.

“The sword of Damocles was hanging over their head for quite a bit,” Bloomfield reflects. “Labour in particular was saying: ‘Look, we’d much rather you did it [reform] but at the end of the day, somebody has to do it.’”

Most of the reforms took place later under James Chichester-Clark whose resignation as Agriculture Minister prompted O’Neill’s own departure: “I think he reached a judgment that O’Neill was fatally wounded and that if progress was going to be made, it would have to be made by somebody else.”

James’ brother, Robin, was MP for Londonderry at Westminster at the time. Robin and O’Neill regularly debated reform at his home. “My then wife grew to dread those conversations,” he told agendaNi. “The coffee went cold.”

In April 1969, Robin refused to put pressure on James – who had by then lost confidence in O’Neill. “Terence expressed his dismay that I had deserted him at last,” he said. Their long political friendship ended at that point.

The roots of the split went back to the afternoon of Remembrance Sunday in 1968.

At James’ home, Moyola Park, the brothers warned O’Neill about Bill Craig’s plotting and pressed him to take forward a fresh package of reforms. The PM saw “no glimmer of hope that he could see anything like our proposals through the Unionist Party” although a number of their suggestions were later adopted.

O’Neill, in Bloomfield’s view, harmed his reputation with his May 1969 interview about Catholics becoming like Protestants if they were treated well: “That seemed to me condescending and it was an unfortunate use of words actually.”

Faulkner succeeded Chichester-Clark as Prime Minister in 1971 and generously kept Bloomfield on his staff. “I came to admire him actually,” he says of Faulkner. “His conduct of affairs was admirable. He was clearly the ablest politician.”

In retirement, O’Neill avoided publicity and probably felt “unwanted and even in danger.” He was elevated to the House of Lords in 1970 and died at his home in Hampshire in June 1990, aged 75.

Legacy

The whole thrust of O’Neill’s speeches, Bloomfield comments, was parity of esteem. “I think he was the first man to speak plainly in those terms,” he recalls. “I think it was very, very important to do that. I mean, it took a long time to realise it institutionally and I think the critic would say: ‘The steps he actually took during his premiership were modest.’ But then you do look at what he was up against.”

“So many of the things that he wanted to do have proved necessary to do ever since,” Bloomfield concludes. “And I think the tragedy of it is that something about his manner and mannerism and personality – and also a degree of innate caution – made it difficult for him to attain all that he wanted to do.”

Robin Chichester-Clark says of O’Neill: “I think his strength was that he had tremendous courage.” However, he could also “give the impression of being cold” and he sees the naming of Craigavon as a mistake: “That was going a little too far to the right.” His predecessor “could have charmed the birds off the trees – and more or less did – but didn’t get things done.” Terence O’Neill, in his view, did not have the charisma of Brookeborough but nonetheless was not particularly over-reserved or snobbish.

To his credit, in Robin’s view, O’Neill was the first politician to stand up against Ian Paisley: “He did his best to fight extremism wherever he found it. It took somebody to do that.”

He also “did not have the greatest people” in his Cabinet with his ministers fearing that they would lose their seats to nationalists and “other extreme Protestants.”

Alasdair McDonnell remembers O’Neill as “an enlightened and decent man” but adds: “He did not understand nationalist frustrations and the humiliations they endured, and mistakenly felt that if treated properly they could become good unionists.”

The SDLP leader views the crossroads speech as “prophetic words that have stood the test of time” and thinks that history “could have been very different if his party had listened.”

Mike Nesbitt recalls hearing O’Neill on the radio as a child. He reflects: “He was not the first, or last, to perish on the twin towers of resistance from reactionary unionism and a republican leadership whose ideology refused him a fair hearing.”

That vision was a major reason for David McNarry’s nudging into politics. “Today Northern Ireland has yet to answer properly the question he put to the country all those years ago,” he remarks.

When civil rights activist Ivan Cooper was elected to Stormont in 1969, he accompanied O’Neill into the chamber to hear the Queen’s speech. “I found him to be extremely courteous and friendly, not at all like a unionist leader,” Cooper recalls.

O’Neill’s political supporters either formed the Alliance Party or continued as the moderate wing within the Ulster Unionists.

Most of his opponents later turned on to a more moderate path, including Faulkner, David Trimble and, indeed, Ian Paisley and Peter Robinson. Many critics were openly sectarian. Others were taken aback by the pace of change and feared the growing militancy within nationalism.

His own assessment on his time in office is recorded in his autobiography, published in 1972. It is probably summed up in the crossroads speech as well: “I have tried to heal some of the deep divisions in our community. I did so because I could not see how an Ulster divided against itself could hope to stand.”

Photo credit: Victor Patterson