How Northern Ireland’s archives work

agendaNi sums up the process for handling public records and the forthcoming change from a 30-year rule to a 20-year rule.

agendaNi sums up the process for handling public records and the forthcoming change from a 30-year rule to a 20-year rule.

The 30-year rule for releasing government files will be reduced to 20 years in a gradual process starting this December. Two years of information will be released at once (e.g. both 1983 and 1984 together in 2013) until the backlog is cleared.

This change followed on from a review, led by Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre, which recommended a 15-year rule. Ministers opted for 20 years as releasing too many files at once would add pressure on the small number of staff involved in this detailed work.

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) is run by the Executive but the law on archives is itself not devolved. The Ministry of Justice at Westminster oversees the three main guidelines used in the release process: the Freedom of Information Act, the Data Protection Act and the Lord Chancellor’s code of practice.

Not all records reach the archives. Civil servants, though, must keep files that give an authoritative account of past actions and decisions, are created due to a legal requirement (e.g. inspection reports) or are needed to protect the legal rights of the department.

Departments keep their own archives and normally send these to PRONI 20 years after the files were first written. As the 30-year point approaches, those files are sent back to the departments.

Officials examine the documents, page by page, to ensure that they contain nothing sensitive. This process usually starts in January or February and the files are returned to PRONI in June or July. Journalists are allowed to review the files in early December and they are then released to the public as the year draws to a close.

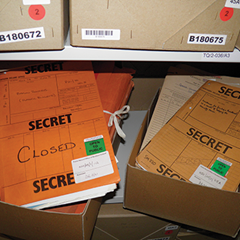

The three most common reasons for keeping files closed are protecting personal information, health and safety, and protecting information provided in confidence.

A serving Minister cannot see a file until it is released but, as a courtesy, a former Minister can be given prior access.

This year, a total of 758 files were released in full. 129 files were partially closed or included redactions. 88 files went back to the archives, for full closure, and some will stay secret for many decades to come.

Many closed files from 1982 cover requests for firearms licences and will remain closed for the next 20 to 50 years. Other files on political and constitutional developments will be held back until 2065 or 2066. Their content could affect the political process, damage community relations or prove uncomfortable for present day politicians.

The oldest unreleased documents are found in a Cabinet Secretariat file covering 1922-1928 and refer to capital punishment and life sentences. Most of the file has been released but the closed part is locked away until 2029.

Political parties are free to comment on the actions of previous governments but their own archives remain private. PRONI holds the UUP and SDLP archives, which can be accessed with their permission. It also holds some DUP, Sinn Féin and Alliance Party material (e.g. election literature) but those parties keep their own records to themselves.

Limits to reporting

Released records are covered by the same copyright and libel laws as other published papers. They are a ‘goldmine’ for historians but naturally contain some errors and cannot fully capture the tone and emotions of meetings held three decades ago.

Media coverage is not necessarily fair as many people featured in the files are now too old or infirm to give their point of view. Jim Prior is now 85, Margaret Thatcher 87 and Jim Molyneaux 92. That said, politicians frequently write lengthy autobiographies in retirement to rebut their critics. Ian Paisley is currently penning his own memoirs: a document that is bound to attract plenty of readers.