Brief respite for public spending

Senior Economist with the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI), Paul Mac Flynn believes that while extra finances secured through the Conservative-DUP deal are welcome, they must be seen context of the challenges that public spending in Northern Ireland already faces.

Following the surprising result of the UK General Election on 8 June, the economy of Northern Ireland has been catapulted to the top of the news agenda. The subsequent confidence and supply deal between the Conservatives and the DUP has attracted criticism from representatives of the UK’s other regions over the £1 billion of new money set aside for Northern Ireland in return for DUP votes in the House of Commons. The deal has also highlighted the broader issue of public spending in Northern Ireland and how the region has fared during the age of austerity. Whilst the new money, if it is eventually realised, will make a difference to Northern Ireland’s infrastructure, public services and the economy more generally, it is worth putting this in the context of the last seven years of public expenditure.

The terms we use to describe public expenditure in Northern Ireland are often conflated and confused. The block grant is what we tend to hear most talk about and that is because it is the amount of money over which Northern Ireland’s politicians have direct control. In reality, it only accounts for 55 per cent of overall direct public expenditure, the other 45 per cent is governed by Westminster, although Northern Ireland’s politicians do have some control over policy in areas such as welfare. The money that was agreed in the Conservative-DUP deal is designed to supplement block grant spending over the next two-to-five years. The deal contains £1 billion of new money and frees up £500 million of other funding that was previously assigned exclusively to specific areas of expenditure.

There is little disagreement over how the money has been apportioned among departments and the £400 million set aside for infrastructure spending along with £150 million for broadband is particularly welcome. However, when it is set alongside the profile of capital expenditure in Northern Ireland over the last seven years, the figures do not seem quite as breath-taking. In 2009/10 the capital budget for Northern Ireland in nominal terms was £1.27 billion and in 2016/17 it was £1billion.

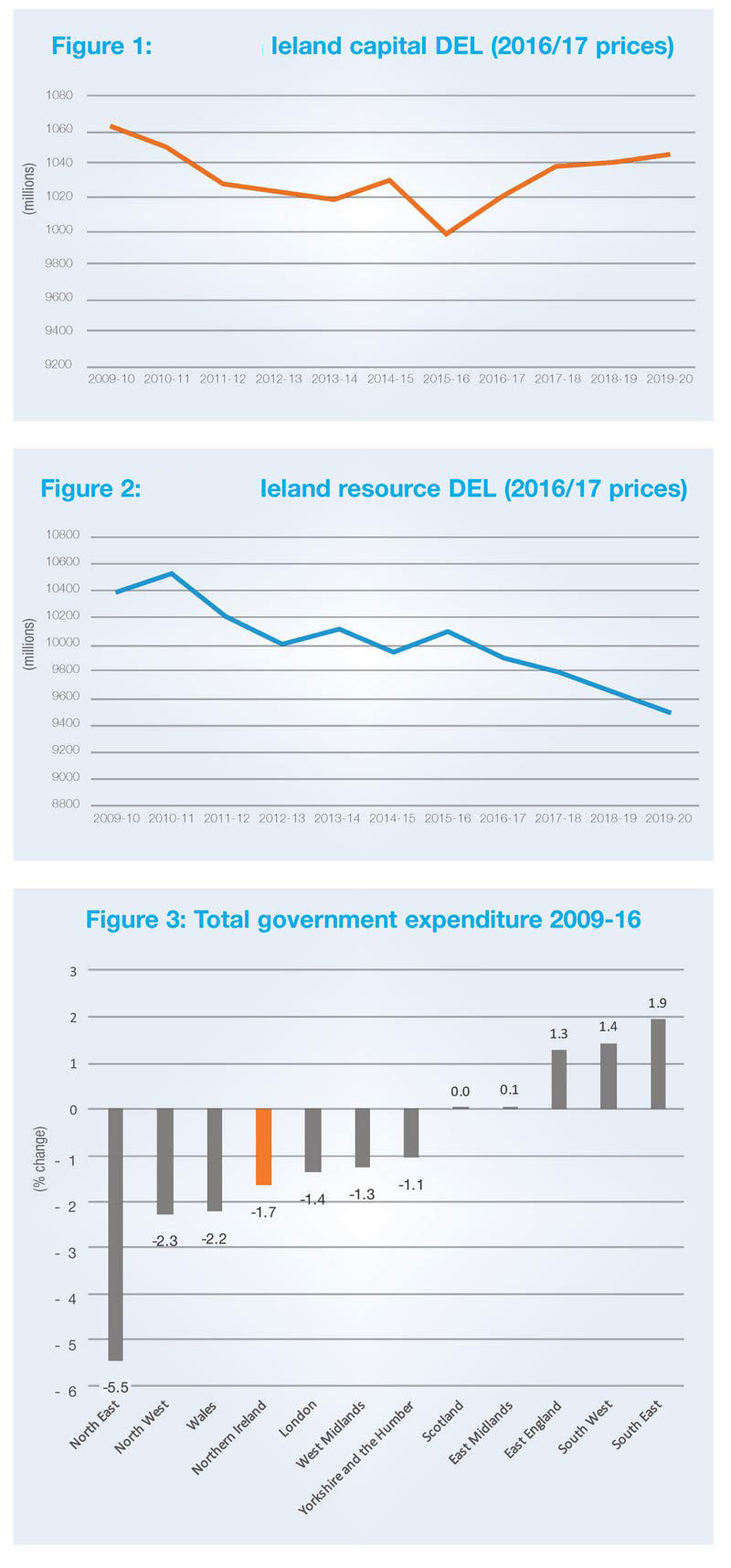

In fact, it fell to a low of £766 million last year and before any deal was agreed it was only set to rise to £1.31 billion by 2019/20. These figures are not adjusted for inflation and as you can see from Figure 1, in real terms Northern Ireland’s capital budget will be considerably smaller by 2019/20. Despite a significant projected increase over the next three years, capital spending is set to be 12.3 per cent lower in 2019/20 than it was in 2009/10.

In today’s money, capital expenditure will be £176 million lower annually by 2019/20. So, while £400 million over two years is an impressive amount, it may only just cover expected losses for those two years. The £150 million agreed for broadband may free up some extra room but in reality, quite a lot of the £400 million is already earmarked for projects like the York Street interchange and other projects which suffered from years of cuts in the capital budget.

Day to day

When we look at day to day spending, the picture is even more stark. Whilst the deal contains up to £450 million for health, education and social deprivation, the experience of budget cuts over the last number of years means that much of this money may simply evaporate on arrival in each of the departments. In 2009/10, day to day funding for public services was £9.3 billion and this year it was £9.9 billon.

More worryingly, the resource budget is set to remain steady at £9.9 billon all the way up to 2019/20. This means a rather large cut when adjusted for inflation as shown in Figure 2. Day to day spending will have fallen by 8.5 per cent in the 10 years up to 2019/20. In cash terms, there will be £885 million less in spending than there was in 2009/10. Taken in this context £450 million appears somewhat lacklustre.

All of this is not to say that the new money from the deal is not welcome, it is. It’s just that it needs to be seen in the context of the challenges that public spending in Northern Ireland already faces. Other regions in the UK voiced concern that they have had to face similar challenges in terms of their public spending over the last number of years and should be equally deserving of new money. This is an entirely valid complaint and anger over continuing austerity featured prominently in the last general election. However, when compared with the other regions of the UK, Northern Ireland has experienced one of the largest reductions in total government expenditure (Figure 3). Whilst voters in the North of England and Wales could take issue, the South and East of England, along with Scotland, have actually performed comparatively better.

All in all, the extra £1.5 billion is good news for Northern Ireland, but it will only provide brief respite for public spending in Northern Ireland. Other regions are right to feel aggrieved, some more so than others, but in reality the entire of the UK would benefit more from an end to fiscal contraction and a new public spending settlement focused on building long term growth.