A renewable fiasco

A renewable heating initiative which will cost the public purse over £1 billion over the next 20 years has been shut down after a damning report by the Auditor General for Northern Ireland.

The non-domestic RHI was introduced in November 2012, parallel to a similar scheme in the rest of the UK, with the aim of aiding the Executive target of achieving 4 per cent of Northern Ireland’s heat consumption from renewable sources by 2015. The scheme offered financial incentive to increase the uptake of renewable heat energy by paying a fixed amount per kilowatt of heat energy for a period of 20 years.

The scheme relied on those wishing to join to purchase a suitable system from an approved installer and then apply to OFGEM, who managed the scheme, almost entirely, for the Department. Originally the UK’s Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP) approved a budget of £25 million for 2011-12 to 2014-15, but initial low uptake saw an underspend of around £15 million up to 2014-2015 and a switch of the Department’s focus to increase demand.

One of the major failings identified by the Auditor General was in 2015, when the Department overlooked seeking re-approval of the scheme from DFP, meaning that 788 non-domestic RHI applications (with an estimated cost of £11.9 million) were passed without consent. An estimated annual expenditure of £19.4 million will have to be funded by the block grant for the next 20 years.

At the time of the DFP approval expiry, the Department witnessed a spike in the number of applications to the scheme and following review, decided upon changes to the tariff to manage demand. However, following the announcement of the new tariff scheme, a 10-week period until operation on 8 September 2015, as many applications were made within seven weeks as had been made in the previous 34 months since the scheme began. The expected cost of the new applications is expected to be £24 million annually for 20 years.

The GB model

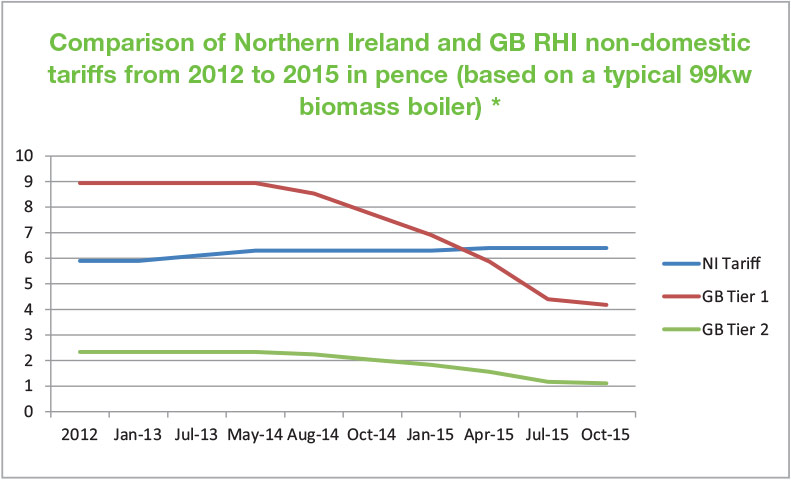

An over-riding theme of the Auditor General’s report suggests that had Northern Ireland followed a similar approach to that taken by GB, expenditure would have been much lower. The GB model operates a two-tier approach, with the higher rate providing a return on the capital cost, while the lower second tier rate minimised incentive to unnecessarily generate heat in order to claim under the scheme. The reduced rate applied after the equipment had been operated for 15 per cent of the hours in a year. In Northern Ireland there was no tiering until November 2015 and the single tariff was higher than the cost of fuel. Another control within the GB model was a quarterly tariff change in response to demand, helping to ensure that excessive profits were not made by applicants. The below graph shows how the Northern Ireland single tariff increased from 5.9 pence in 2012 to 6.4 pence in 2015, while the two tariffs in GB halved over the same period.

The rate of inspection in Northern Ireland was estimated at 0.86 per cent of applications, compared to 1.86 per cent in GB.

Concluding his audit of the DETI Accounts 2015-16, Comptroller and Auditor General, KJ Donnelly said: “This scheme has had serious systemic weaknesses from the start. The fact that the Department decided not to mirror the spending controls in Great Britain has lead to a very serious ongoing impact on the Northern Ireland budget and the lack of controls over the funding has meant that value for money has not been achieved and facilitated spending which was potentially vulnerable to abuse. I am very concerned about the operation of this scheme and it is an area which I expect to return to in the very near future.”